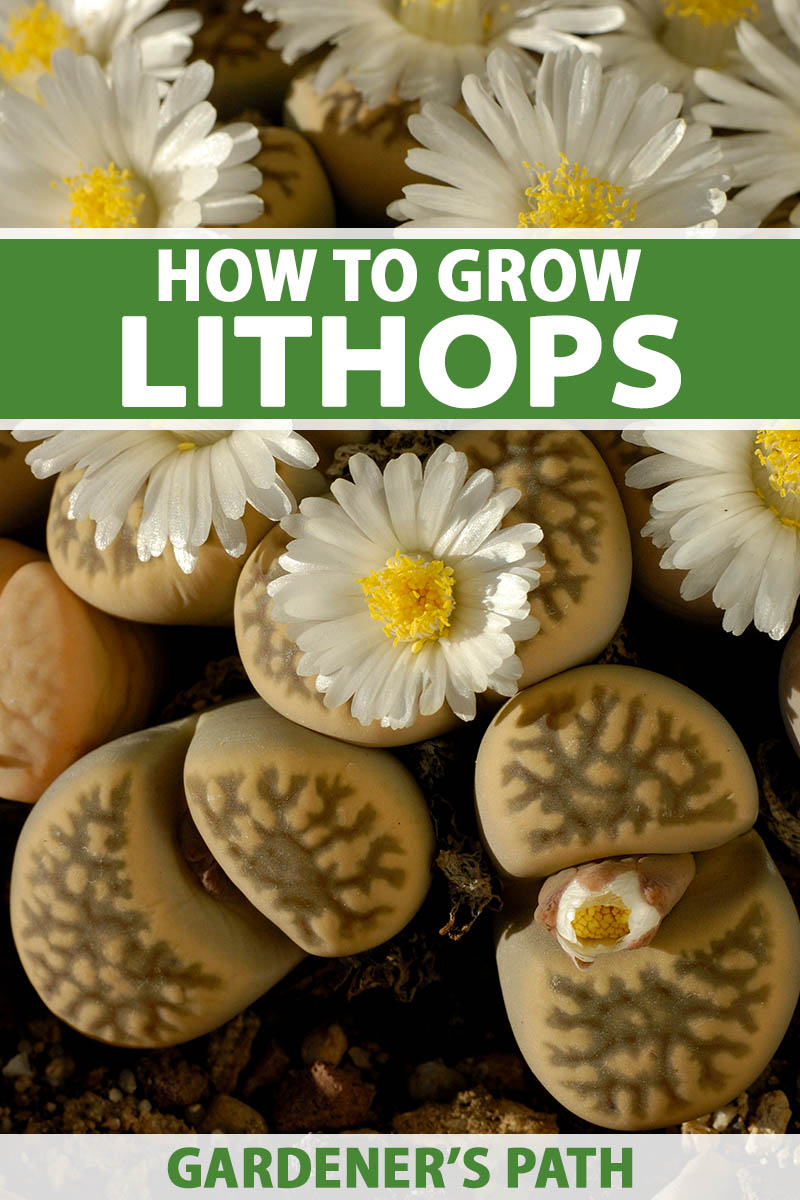

Lithops spp.

Have you ever joked about wanting a pet rock? How about a living stone, instead? And yes, I’m talking about growing lithops succulent plants!

Masters of mimicry, living stones are fascinating succulents, but these quirky little plants also have quirky little care routines.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

You will certainly want to learn what is required of you before you acquire one of these – or as soon as possible after bringing a lithops home!

Ready to find out how to grow and care for living stones? Here’s what we’ll cover:

What Are Lithops?

If you were to ask a child to make a drawing of a plant, you’d likely get an image of a stem with big green leaves.

The subject of our article couldn’t be further away from this verdant vision of planthood – and most living stones are not even green!

There’s a reason for that.

These succulent plants camouflage themselves as stones, appearing in very muted colors to help them blend into their surrounding natural habitat of rocky, gravelly terrain.

Referred to as “mimicry plants,” lithops have evolved this growth habit to hide from hungry animals hunting for leafy green foods.

This low-profile growth habit also allows lithops to protect themselves from their harsh climates, as the bulk of the plant is located underground.

Lithops Anatomy and Markings

Lithops are unusual plants and describing them requires specialized terms.

To better understand them and to appreciate the appearance of the different living stone species and cultivars, it’s worth taking the time to learn what these terms mean!

Bodies or Heads

The “body” is the fleshy part of the lithops plant, not including its roots. Part of the body grows underground, while the rest is visible aboveground.

The bodies of these plants – made up of two fused leaves – are about two inches tall, more or less, and are shaped like hearts, double wedges, or inverted cones, with the pointy, downward end giving way to small roots.

Depending on the lithops species, only the top half-inch or so of the body may emerge from the ground, while some are rather elongated, with more of the plant above the soil line.

The bodies of these succulents range in width from about half an inch to an inch and a half wide, depending on the species.

The term “head” is another term for body, but usually refers to the part of the plant that is above ground.

Some living stone species produce just one head per plant during their entire lives, while others may produce clumps made up of dozens of heads.

Lobes and Faces

Lithops bodies are made up of two thick, fleshy, fused leaves, called “lobes” – two lobes make a head.

The lobes of some species are equal in size, while others are slightly (or quite) asymmetrical.

Additionally, there is variation as to the depth of the fissure between the two lobes – with some having a shallow cleft and others a deep one.

Likewise, some lobes grow close together (these are described as “flush faces”), while others are divergent, with a wide gap between the two lobes.

The tops of the living stone lobes, when viewed from the side, can be either more or less flat, or rounded.

Note that this appearance can change when the plant is well-watered, in which case the lobes may become more convex, or when the plant is thirsty, when the tops of the lobes may become slightly concave.

Looking down on them from above, lithops heads are more or less round or oval shaped, and viewed from this angle, each leaf is known as a “face.” Each head or body has two faces.

These faces can have half-circle, half-oval, kidney, or even slightly rectangular shapes.

Some faces have smooth surfaces, others are rough and can be textured with furrows, bumps, warts, wrinkles, or pits!

Fissures and Molting

Both flowers and new leaves emerge from the slit (usually referred to as the “fissure”) between the two fused leaves, each at different seasons in the year – most lithops species produce flowers in autumn and new leaves in spring.

When new leaves emerge, the body goes through a process called “molting” (similar to that of animals), in which the old leaves dry out and are shed to make way for a new set of leaves – or sometimes a double set of leaves.

This results in some living stone species eventually having many heads on one plant.

Flowers

As for lithops blooms, only one flower is produced per head, and this is held facing the sky on a very short stem.

Flowers are daisy-like, and usually yellow or white – or yellow and white. In some species, flowers can be shades of bronze or pink.

These emerge in fall in most species, and in bright sun, usually at noon.

Windows

To make up for keeping their leaves mostly underground, the top part of each lobe has what is known as a “window” – a translucent section of the face.

Windows are also sometimes called “seas” or “lakes.” These windows allow light into the plant, where photosynthesis takes place.

If you were to cut a lithops in cross section from top to bottom, you’d find translucent tissue inside the leaves below the windows, as well as green tissue lining the inside of the body.

This window is more visible in some species than in others. Some are unobstructed and broad, taking up most of the face – plants like these are sometimes referred to as having “open” windows.

On the other extreme, some lithops have windows that are completely opaque looking, often referred to as being “absent.”

Most lithops, however, have markings on them that obscure the windows at least somewhat.

Sometimes small round dots of window are present among the opaque markings, and these are called “miniature windows.”

There are special terms used to describe these markings.

While you don’t have to know these terms to enjoy your plants, understanding what these words refer to can help you appreciate what makes different species, subspecies, and varieties distinctive!

Ready to learn more about these markings?

Islands and Peninsulas

Many living stones have “islands” on their faces. Imagine that the window is a body of water – the islands are opaque markings that seem to float in this body of water.

Islands can be large or small, few or numerous, and their edges can be more or less rounded, or quite jagged.

As they do in real bodies of water, “peninsulas” on living stones jut out from the edges of the face into the window.

Margins and Shoulders

Margins are bands of color around the windows, or, in the absence of windows, along the edges of the face.

Living stone plants sometimes have both inner and outer margins but not all species have discernible margins.

Sometimes living stone margins are the same color as the body, sometimes they are different colors.

The term “shoulders” is used to describe the edges of the lithops face, beyond the outer margins. The shoulders are sometimes yet another color.

Channels

Some windows have so many opaque markings obscuring them that the window parts that are still apparent get a name change and are referred to as “channels.”

Channels can be narrow or broad, are sometimes furrowed into the face’s surface, and are sometimes lined with additional markings.

Dusky Dots

Some species have what are called “dusky dots” decorating their surfaces.

These can be indented, flush with the surface, slightly raised, or very much in relief, in which case they may be referred to as “warts” or “pimples” depending on how big they are.

Dusky dots can be dark gray, dark green, or brown.

While there are sometimes small, dot shaped windows on the face, those are translucent while dusky dots are opaque.

Rubrications

Many species of lithops have dark reddish patterns on their faces, called “rubrications.”

Rubrications can be in the form of lines, dots, checks, or stars, and they often line channels, creating either a connected network of patterns, or a broken network.

Note that not all of these features are found on each plant. The combination of these markings along with their anatomical characteristics is what allows these miniature marvels to be distinguished from one another!

Cultivation and History

Lithops hail from southern Africa, with populations native to Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa.

In the wild, they grow in habitats composed of bare rocky ground, dry grassland, and scrubland. The soils in their native environments tend to be rocky and sandy.

These succulents have adapted to conditions with little rain. Their native regions receive an average of 20 inches of rain per year or less.

Populations of lithops in some locations get less than four inches of rain a year, and some are watered primarily by fog and mist.

However, most species originate in climates that are hot in the summer, with autumn rains, and cool or cold winters.

Lithops are members of the ice plant family, or Aizoaceae – also known as the “fig marigold” family.

Members of this family include ice plant (Delosperma lehmannii) New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides), and baby toes (Fenestraria spp.).

Relatives from this family include additional mimicry plants which may be attractive to succulent collectors – such as Conophytum, Dinteranthus, and Pleiospilos species. The members of the Pleiospilos genus are known as “split rock plants.”

The genus name Lithops comes from the Greek and means “stone face” or “resembling stones.” These succulents are also known as “pebble plants” or “living stones.” For reasons that should need no explanation, some also call them “butt plants.”

The subject of our article, as well as some other members of this family are often called “mesembs,” which is short for Mesembryanthemaceae, a synonym for Aizoaceae.

Mesemb is commonly used as a synonym for the expression “mimicry plant” – both of these terms are used for other members of the fig marigold family as well as lithops.

Speaking of plant families, lithops were first classified taxonomically in 1922, making them relatively recent arrivals to the houseplant scene.

There are around 37 species in the Lithops genus, as well as many subspecies, naturally occurring varieties, and cultivars.

Currently lithops populations are under increasing threat in the wild due to habitat loss and poaching.

While plant collecting is a fun hobby, be sure to limit your purchases to specimens that are nursery grown rather than obtained through poaching wild specimens.

Interestingly, these diminutive succulents can live to be quite old in cultivation – up to 50 years – joining the ranks of other long-lived houseplants such as Christmas cacti and hoyas.

While succulent enthusiasts can grow these plants indoors, lithops can also be grown outside year round in USDA Hardiness Zones 9b to 11b, provided you can protect these drought tolerant plants from receiving too much water.

Lithops Propagation

There are two ways to propagate lithops – from seed and by dividing plants, both of which are easy methods. Let’s look at each of these:

From Seed

Late spring, late summer, and early autumn are all good times to propagate living stones from seeds.

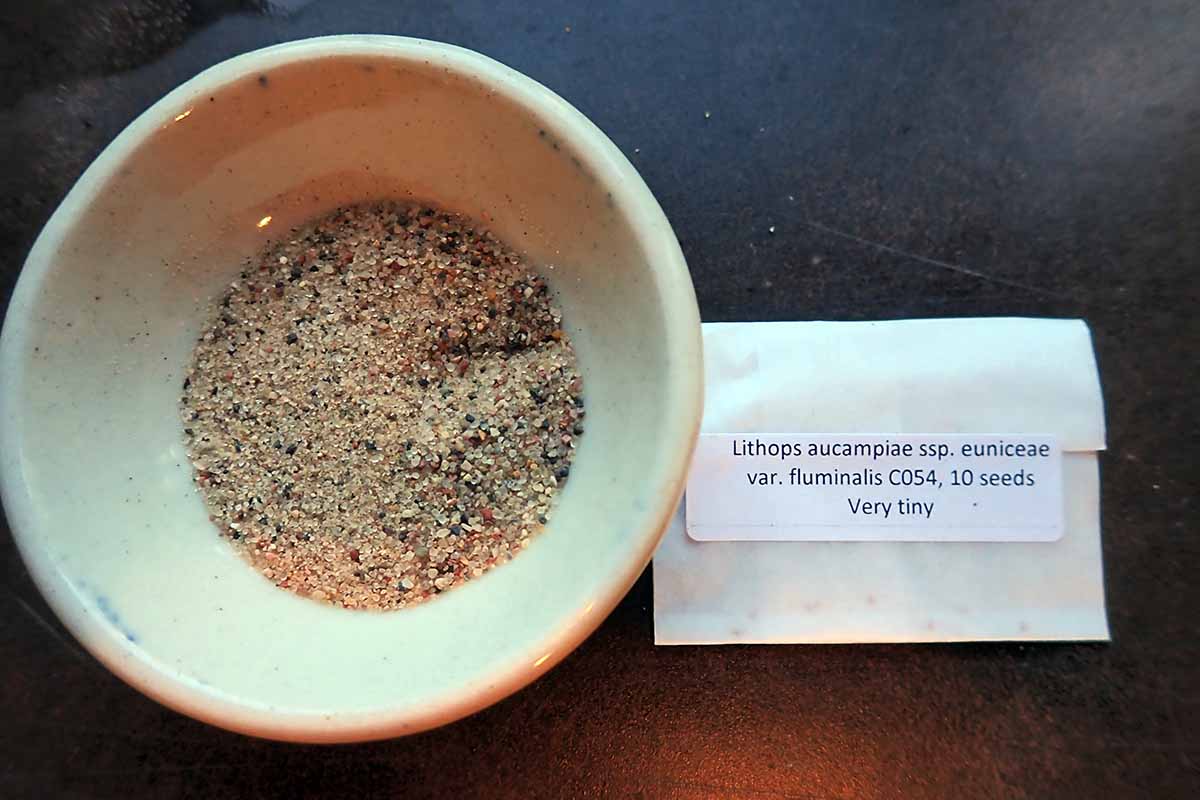

Here’s what you’ll need for this project: lithops seeds, fine sand, small river rocks or coarse silica sand, three- or four-inch nursery pots or a propagation tray, a spray bottle filled with water, a humidity dome, and growing medium designed for cacti and succulents.

While adult lithops can be grown in a gritty, mostly mineral based mix, seedlings need a medium with a bit more moisture retention.

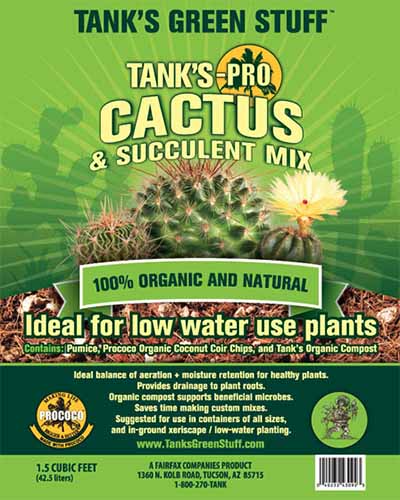

An ideal mix for this purpose is to combine one part coarse silica sand with two parts cactus and succulent potting medium, Tank’s-Pro Cactus and Succulent Mix, available in a 1.5 cubic foot bag via Arbico Organics.

Tank’s Pro Cactus and Succulent Mix

First, fill nursery pots with growing medium, leaving an inch and a half of space between the top of the growing medium and the rim of the pot.

Once you have filled the nursery pots or tray with the growing medium, go ahead and water it down.

Next, on top of the growing medium place a half-inch layer of small river rocks or coarse silica sand, such as this coarse silica sand available from Miukada in 3.3 pound bags via Amazon.

Now mix the very tiny lithops seeds with about a tablespoon of fine sand – you can sow 10 to 30 seeds per pot.

Sprinkle this sand and seed mixture onto the layer of small river rocks, then moisten the fine layer of sand with a few gentle mists from a spray bottle.

Finally, cover the pots or tray with a humidity dome. You can use transparent plastic bags for this, or you can cover the pots with plastic wrap. Secure the plastic wrap or bags with rubber bands.

If you are using plastic wrap or plastic bags, poke a few holes in them with a toothpick to provide some ventilation.

Molded plastic humidity domes usually come with vents – you just need to open them slightly.

Locate the pots at room temperature in indirect, bright light to germinate. Although they’ll be able to survive in full sunlight once they are established, young seedlings will be scalded by direct sun.

Keep an eye on the humidity dome, plastic bag, or plastic wrap covering your pots. When condensation disappears from this covering, it’s time to water again.

Remove the covering and gently spray the growing medium with a water bottle to keep the humidity high, then replace the covering.

Expect germination to start in five to ten days, though some seeds will be much slower to germinate – some can take up to a year, so make sure you sow more than you need.

Two weeks after germination, gradually transition the seedlings to ambient conditions by removing the humidity dome for an hour the first day, increasing the amount of time exposed to drier air each day.

Water the uncovered young seedlings daily by spraying their growing medium with a spray bottle.

Two to three months after the seedlings have germinated, progressively increase the time between waterings, allowing the growing medium to dry out for a few days.

Wait 18 to 24 months before transplanting seedlings to different pots.

From Division or Transplants

While many succulent collectors value multi-headed lithops specimens, some houseplant parents may wish to experiment with dividing these plants.

Living stones that have more than one head can be propagated in this way.

Remember, each head is made up of two leaves. Some species can form multi-headed plants, but not all.

So, just to be clear – don’t split a single head apart, instead, wait until a plant has at least two heads – or in other words, at least two sets of fused leaves.

The best time to divide is after the plant has finished molting in spring.

Here’s what you’ll need: small pots, coarse silica sand, a butter knife, a sharp pair of sterilized scissors or garden pruners, and lithops growing medium.

You’ll learn more about creating a suitable growing medium for living stones later in the article, so keep reading to learn more!

When you’re ready to divide, first prepare small pots for transplanting, such as these two-and-a-half-inch ceramic pots with bamboo saucers, available via Amazon.

Pack of 6 Glazed Ceramic 2.5” x 2.15” Succulent Pots

Fill the pots with growing medium, leaving an inch of space at the top.

Remove the lithops from its pot, then gently remove the growing medium from the plant’s roots.

Now, gently separate the heads from each other at the roots, you may need to cut them apart with sterilized scissors or snips.

Remove any dry leaves or dead flower stems from the body, then allow the heads to dry for an hour before continuing.

Use the butter knife to make a hole in the growing medium, and insert one of the heads into the hole, root side down.

Wondering how deep to plant the lithops in the soil?

The soil level should reach approximately to the leaf fissure. Depending on the species or cultivar, the plant will be mostly buried with only the top inch or half inch above the soil line.

This will vary depending on the species, so it’s best to know which type you have!

Finish up by adding a half-inch layer of coarse silica sand or fine river rocks to the surface of the growing medium as a mulch. This will help keep the upper portion of the plant body dry.

Repeat the process with any additional heads, or simply return the parent plant to its pot, filling in with extra growing medium if needed.

For lithops that have been divided, give them two weeks after division until providing them with water.

After two weeks have passed, water them every 10 days for the next two to three months, at which point they should be well-rooted in their new pots.

How to Grow Lithops

Lithops don’t need frequent care, but their care does require more mental effort and planning than the average houseplant.

In this section you’ll find general lithops care that will work for the majority of the species – there are some exceptions, however, so be sure to check specific directions for your chosen species.

Sun

Lithops can be grown in direct sun, or a mix of direct sun and bright, indirect light.

Aim for at least four to five hours of direct sun per day. This preference makes living stones great candidates for life on a south-facing windowsill since they also don’t mind cooling off a little at night.

However when moving specimens grown in partly shaded conditions to greater direct sun exposure, do so gradually, otherwise they can be damaged by sun scald.

Also, if your home gets particularly hot during summer due to lack of air conditioning, decrease the plant’s exposure to direct sun.

You can do this by fitting the window with a sheer white curtain which you close for part of the day or moving the plant farther from the window.

Climate

As for climate, lithops tolerate a wide range of temperatures, from highs of 107°F down to sub-freezing temps of 23°F, but exposure to these extremes should be limited.

They will also be happiest in low humidity with good air circulation.

Water

The amount of water living stones will need depends on how much direct sun they are receiving, how hot the indoor environment is, how moisture retentive their growing medium is – and the species!

The most important thing to know is that you should err on the side of underwatering rather than overwatering.

In general, if your plant starts to shrivel a bit and feel soft, it might be time to water.

However, before you pick up your houseplant watering can, there’s also a seasonal watering schedule you’ll need to know about first.

Late summer to autumn is when the majority of living stones need the most water, before they begin to bloom and while flowering.

Starting in late summer, water once every two to four weeks, allowing the growing medium to dry out between waterings.

Note that young specimens may not flower, but still need to be watered during this period.

Whether it flowered or not, in winter most lithops species go through a dormant period and it’s important to withhold water during this season. Or at the most, if the plant is shriveling, offer a very light watering of a few drops or a light misting of the growing medium.

In late winter or early spring a living stone will start to molt, shedding its old skin to produce a new pair of leaves, or two new pairs of leaves.

It’s important not to water at this time. The new growth will take the moisture it needs from the old growth, leaving the old leaves to turn into a thin, desiccated skin.

This process is necessary for the new growth to emerge properly – if you water, you’ll prevent the old growth from drying out.

Once the living stone’s old leaves have completely dried up, begin to water again, approximately every two weeks, allowing the growing medium to dry between waterings.

When conditions start to get hot in summer, the plant will experience another dormancy period, and watering should be withheld or at least, reduced. Water only if the plant is shriveling, and if it’s very hot, reduce direct sun exposure somewhat as well.

Begin watering again in late summer – and continue the lithops’ yearly cycle.

If you’re having a hard time keeping track of the watering schedule for this plant, consider keeping notes in the calendar section of a gardening journal.

How do you know if you’re watering a lithops too much?

Overwatered living stones can develop diseases and sometimes even burst – but the first sign you’ll notice is elongation.

However, note that some species are naturally elongated, so it pays to know the typical characteristics of the species of lithops you’re growing so that you can correctly spot when something goes wrong!

Once a plant has been affected by overwatering, there is little that can be done to return the plant to its former glory, making proper watering your first step in keeping these succulents healthy.

Soil

Of course, these succulents are also less likely to suffer the effects of too much water if they are cultivated in the right type of growing medium.

Since lithops’ native habitats consist of rocky, gritty, sandy soils, you’ll want to try to mimic those conditions when choosing a growing medium.

Avoid growing mediums that contain non-renewable peat, which is not an appropriate ingredient for these succulents anyway.

To learn more about what professional lithops growers use in the way of growing mediums, I reached out to Jane Evans, co-owner of Living Stones Nursery in Tucson Arizona, a business which only sells to local customers.

Evans told me that their lithops potting mix is essentially 50 percent cactus mix and 50 percent pumice.

Pumice is a great horticultural ingredient to have on hand when your love for houseplants is turning into – well, let’s call it a hobby.

You can purchase an eight-quart bag of horticultural pumice from Tank’s Green Stuff via Amazon.

So keep this 50:50 ratio in mind when creating your own succulent potting soil for transplanting, dividing, or repotting your living stones. A ready-to-use, commercial cactus and succulent soil in itself is not quite right for lithops. Additional grit is required.

Growing Tips

- Provide at least four hours a day of direct sun.

- Water during late summer and autumn, and during spring after old leaves have dried.

- Grow in a gritty potting medium with excellent drainage.

Maintenance

As we’ve already discussed, the best way to care for your living stone is to know what to expect from it throughout the seasons so that you can provide water at the appropriate times.

Here are a few other answers to maintenance questions you’re bound to wonder about!

Mulch

A mulch of gravel or coarse sand is typically added to the top of the growing medium. This keeps the living stone’s head dry and also helps to keep the plant upright.

If your lithops growing hobby is turning into a passion, you might want to choose gravel composed of the same types of rocks from your species’ native habitat to provide it with five-star care.

You might even go so far as to choose gravel that matches the color of their plant, to show off its prowess as a mimic!

Fertilizing

Fertilizing is not necessary with these succulents, which evolved to thrive in poor soils. Some professional growers fertilize frequently, however, and others do so very rarely or not at all.

One option for home growers of living stones is to offer a gentle fertilizer when repotting, such as Dr. Earth’s Succulence Organic Pump and Grow Cactus and Succulent Plant Food.

Dr. Earth’s Succulence Pump & Grow

It’s available in a 16-ounce pump bottle via Arbico Organics.

Repotting

You won’t have to repot your living stone very often – on average, only about once every two years if it needs extra room because it’s producing multiple heads.

When choosing a pot, shallow pots are preferable, but they’ll need to be at least two inches tall to accommodate the large portion of the plant that grows underground. Those that are two to three and a half inches tall are ideal.

You can repot lithops into small, individual pots, or include them in a wide, shallow succulent dish, either with other lithops or with some easy-care succulent buddies – just make sure to choose succulents with similar water and humidity needs.

If your living stone still has plenty of room in its container, sufficient drainage, and the container is to your liking, the plant will be happy to remain there permanently.

However, older specimens with multiple heads should be repotted as their pots become crowded.

Encouraging Flowering

If you’ve propagated a specimen from seed, don’t expect flowering until the plant is two or three years old.

To encourage flowering, make sure the plant receives adequate sunlight.

Flowering is sometimes better on specimens grown in small, individual pots rather than wide dishes – though not all growers find this to be true.

Saving Seeds

If you’re hoping to produce living stone seeds for propagation, know that you’ll need at least two specimens since they need to cross pollinate.

To save seeds, after flowering make sure to bottom water. This is because water droplets hitting the top of the plant will cause the seed pods to open, releasing seeds.

Allow pods to fully mature and dry out before harvesting them, then store seeds for at least one year before planting. Seeds will remain viable for many years.

Lithops Species and Varieties to Select

There are many species, subspecies, naturally occurring varieties, and cultivars of lithops available to succulent collectors without bothering with the loathsome practice of poaching wild specimens. Here are a few of interest:

Karasmontana

L. karasmontana is a species that was bestowed with the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit in 2002.

With a lot of variability, the species can appear in shades of brick red, beige, yellow, brown, pink, grayish white, or grayish green.

This species usually produces two to six heads, but can sometimes be found in mature clumps of 12 or more.

Their faces have a bumpy texture. Kids (and the young at heart) may get a kick out of these because some specimens can look rather like brains!

‘Top Red’ is a cultivar of L. karasmontana that has a beige to gray body, and broad, furrowed, brick red channels.

Lithops Karasmontana ‘Top Red’ Seeds

Want to try growing your own from seed? You can purchase 50 L. karasmontana ‘Top Red’ seeds from Dichondra via Amazon.

Otzeniana

L. otzeniana is a species that is usually found in an olive green color, but can also appear in muted shades of pink, cream, or blue.

This living stone has a deep fissure between its two leaves, and lobes that are slightly divergent.

With distinct margins around its translucent windows, L. otzeniana has large rounded peninsulas and islands framing its windows.

L. otzeniana bears yellow flowers with white centers.

If you’re ready to propagate your own, you’ll find packs of 15 L. otzeniana living stone seeds for purchase via Amazon.

Rubra

A cultivar of L. optica, ‘Rubra’ is milky pink to reddish purple in color, with translucent windows and smooth faces.

There’s a very deep fissure between the two leaves, which gives this plant a different profile than many other lithops species.

This living stone’s beautiful faces are smooth with broad, dark purple or reddish windows, and distinct margins. They usually lack islands.

The flowers of L. optica ‘Rubra’ are white, and often have pink tips.

Got your eye on these living stones? You can keep them well within view – purchase a three pack of one- to two-year-old L. optica ‘Rubra’ lithops via the Micro Landscape Design Store via Amazon.

There are many more types of living stones available to cultivate at home or to admire from afar. Discover more in our guide to 37 different types of lithops. (coming soon!)

Managing Pests and Disease

When it comes to pests and diseases, expect healthy lithops specimens to remain pest free.

However, be on the lookout for mealybugs, scale, thrips, aphids, and spider mites. Fungus gnats can be a problem for young seedlings which are kept in more humid conditions.

Rot is the only real risk of disease for this succulent, and can be prevented with proper watering, the right soil, and excellent drainage.

Read our article about rotting in succulents to learn more.

Best Uses for Lithops

As discussed above, lithops make great windowsill plants, and would be adorable as part of a tiny plant collection. You might also consider including them in a succulent fairy garden!

They can also be incorporated into wide, shallow succulent planters with other specimens, as long as the other plants have similar water and soil requirements.

Outdoors lithops can be grown in rock gardens with cacti and other succulents in USDA Hardiness Zones 9b to 11b, provided they are given the right soil and moisture conditions.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Succulent | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, yellow, pink, bronze / foliage colors extremely variable |

| Native to: | Southern Africa | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 9b-11b | Tolerance: | Drought |

| Bloom Time: | Autumn | Soil Type: | Rocky, gritty, sandy |

| Exposure: | At least 4 hours direct sun | Soil pH: | 5.6-10.0, depending on species |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Soil Drainage: | Extremely well-draining |

| Spacing: | 1-2 inches, depending on species | Uses: | Rock gardens, succulent collections, succulent fairy gardens, succulent planters |

| Planting Depth: | Top 1/2 inch or so of plant above growing medium (plants), surface (seeds) | Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Height: | 1/2-2 inches, depending on species | Family: | Aizoaceae |

| Spread: | 1/3-2 inches per head, depending on species | Subfamily | Ruschioideae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Lithops |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, fungus gnats, mealybugs, spider mites, thrips; Rot | Species: | Aucampiae, fulviceps, hookeri, localis, optica, otzeniana, salicola, viridis |

Lithops – Much More Fun Than a Pet Rock!

Living stones are unique and compact succulents that make excellent houseplants provided you have plenty of sunlight and just the right amount of restraint with the watering can.

And while for most of the year they may look like nothing more than pet rocks, you’ll know these living stones are ready to produce magic throughout the seasons – beautiful flowers, and sets of fresh new leaves.

What do you love most about lithops? Their petite statures, or their mesmerizing patterns? Tell us in the comments section – and if you need help troubleshooting, let us know, we’d be happy to help!

Want to keep learning about cultivating cacti and succulents? Have a read of these guides next: