The Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, is one of approximately 180 flowering carnivorous plants in the Droseraceae or sundew family.

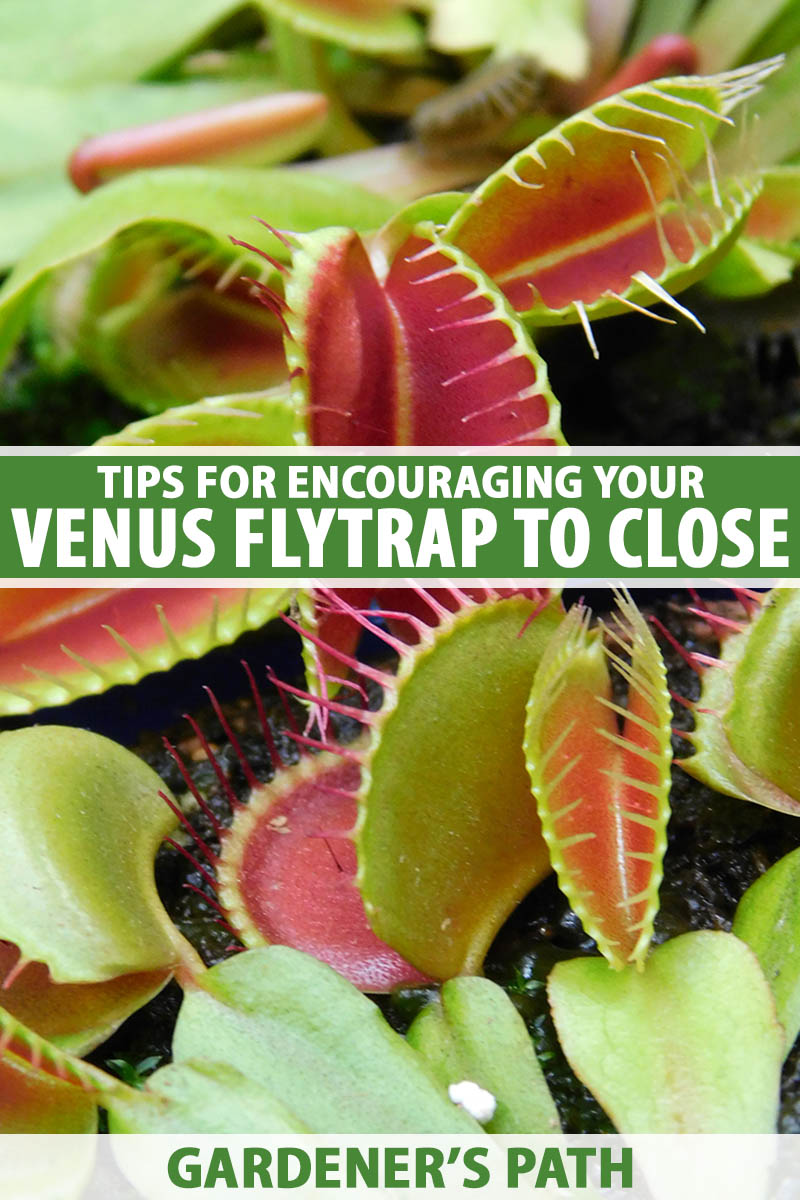

It’s a species right out of a science fiction story, with a gaping red mouth and jagged jaws ready to chomp down on unsuspecting insect prey.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In our guide to growing Venus flytraps, we cover how to cultivate these unique plants at home.

This article discusses how to encourage Venus flytraps to close so you can witness their most fascinating feature.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Let’s learn about this carnivorous wonder of the plant kingdom!

Cultural Requirements

Venus flytraps are flowering perennials native to the bogs of North and South Carolina.

They are winter-hardy in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 10 and may survive in Zones 5 and 6 with cold-weather protection. They can be grown as houseplants in all zones.

The species performs best in full sun to part shade, moderate humidity of approximately 50 percent, and consistently moist, acidic, nutrient-poor soil.

Those cultivating indoors should grow it in equal parts of whole-fiber sphagnum peat moss and sharp sand or coarse vermiculite.

Ideal cultivation temperatures are 70 to 95°F during the growing season and conditions as low as 40°F are tolerated during winter dormancy.

During the dormant season, remove all blackened foliage and water minimally.

In the spring, leafless stems up to 12 inches tall bear upturned, fragrant white blossoms. The foliage grows in a mound at the base of the plant and consists of stalks with terminal leaves.

Mature heights are six to 12 inches with a spread of six to eight inches.

The leaves are hinged and have double lobes with bristly, jagged margins. The inner side of the leaves is reddish, sticky, and dotted with two to six trigger hairs.

Like other plants, flytraps feed themselves via photosynthesis and by the roots’ uptake of soil nutrients. A primary macronutrient is nitrogen.

Nitrogen is limited in the bogs where flytraps grow, so evolutionary changes led to the adaptive behavior of attracting and consuming insect prey.

Carnivorous Behavior

Scientists describe flytrap leaf pairs as curved, hydroelastic “shells.” The leaves are flexible and concave or inward-curving.

These hydroelastic layers are kept under hydrostatic pressure, and it’s the change in pressure that causes the leaves to open and close.

Open leaves contain stored energy. When an insect triggers the hairs, a process known as “thigmonasty” occurs, which is an involuntary closing of the leaves, during which the “turgor” or water pressure changes, and water flows between the leaf tissue layers.

The stimulation of the trigger hairs plus insect secretions set off mechanosensors that signal plant motor cells to act and produce digestive enzymes.

A trap can close partially or entirely, depending upon the energy level required to contain the prey.

A semi-closed trap generally reopens in 12 to 24 hours. A fully closed one may take five to seven days to reopen. Any given pair of leaves can open and close up to 10 times before withering and turning black.

Remove dead traps during the growing season to redirect plant energy to produce new foliage.

A Scientific Perspective

Flytrap behavior is widely studied. In addition to botanical interest, engineering applications abound for nature-inspired biomimetic robotics.

In 1873, the Royal Society of London published “Note on the Electrical Phenomena Which Accompany Irritation of the Leaf of Dionaea muscipula” by doctor and physiologist Burden Sanderson.

Using a galvanometer, Dr. Sanderson detected and measured electrical impulses traveling through Venus flytrap leaves and stalks during trigger hair stimulation.

For a Venus flytrap to close, the trigger hairs must be stimulated twice in thirty seconds. Such rapid movement causes the phenomenon Dr. Sanderson observed and tested, which we call “fast electrical signaling” today.

Contemporary studies of the phenomenon refer to this groundbreaking work, and there is still much to learn about plant complexities at the cellular level.

Twenty-first-century scientists have established that the ideal pH for the trigger response and leaf closure is 4.5, as you would expect in peat-rich but nutrient-poor bog soil.

Prompting the Trigger Response

Gardeners who cultivate flytraps outdoors are more likely to witness closing than those who grow them indoors where there are fewer insects.

To encourage flytraps to close, make sure you meet their needs for nutrient-poor, bog-like, acidic soil; consistent moisture; moderate humidity; and ample sunlight or bright, indirect light indoors.

Avoid fertilizer. Well-fed plants have no reason to “hunt” for prey and will likely not expend energy doing so.

Monitor for pests, like aphids and spider mites, and diseases, like black spot, and treat all promptly with organic insecticidal, fungicidal neem oil.

When Dionaea muscipula is stressed it may divert energy away from trapping behaviors.

If the leaves on your houseplant are not closing, you can hand-feed live insects. The New York Botanical Garden recommends crickets, flies, slugs, and spiders that are less than one-third the size of the trap.

Never feed non-food items, meat, large pests, and insects likely to crawl away. Avoid dead bugs, as they lack digestion-stimulating secretions, and lack nutrients.

If you haven’t got the stomach to feed live food but want to witness the closing response, you can use a cotton swab to nudge the trigger hairs gently. Studies show that using slow movements, followed by fast, then slow again best simulates a writhing insect.

While fascinating, note that the energy expended to close an empty flytrap doesn’t provide nourishment and shortens the life of the stem and leaf.

A Hungry Little Monster

Carnivorous flora like the Venus flytrap amaze us because they seem to cross the line between flora and fauna.

They evolved to feed themselves when nutrients in their native environment were inadequate and are the inspiration for numerous horror fantasy stories.

When you provide your D. muscipula with its ideal cultural requirements, it may not need to expend energy capturing prey. But if you want to watch the devouring mechanism, you now know how to feed your hungry little monster.

Are you growing these carnivorous plants? Have you observed your Venus flytrap closing? Let us know in the comments section below!

If you found this article helpful and want to read more about carnivorous plants, we recommend the following: