Has your previously perky, lush, and green houseplant suddenly turned sickly yellow and droopy, or are there brown areas on the foliage and dropping leaves?

Root rot is a common issue in houseplants. Because they’re grown in such small environments compared to what they’d experience in nature, they’re a lot more sensitive to extremes such as too much water. And too much water is a direct cause of root rot.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Pretty much any species is susceptible to root rot, though some are more resilient than others.

Coming up, we’ll help you figure out if your plant has root rot and what to do about it.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

Managing Root Rot in Houseplants

Before we figure out how to identify it, let’s talk about what causes root rot.

Causes of Root Rot

There are two main causes of root rot. The first is an abiotic condition when there is so much water in the soil that the roots literally drown.

When the soil is oversaturated, the roots aren’t able to access enough oxygen, and they start to turn soft and mushy. Just like any other creature when it’s deprived of oxygen – the plant starts to die.

In addition, there are many different fungi and water molds (oomycetes) that can cause the problem, but Fusarium spp., Pythium spp., Phytophthora spp., Rhizoctonia spp. are the most common and attack the broadest range of plants.

All of these pathogens thrive in high moisture and can be spread via water, in contaminated soil, on contaminated tools, and by insects, particularly aphids. The pathogens enter the plant via damaged vascular tissue.

The pathogens aren’t airborne, but if you have a humid home or growing area, they can spread through the water droplets in the air.

Symptoms

The symptoms of this disease can vary depending on the species affected. But in general, you’ll see yellowing leaves, brown patches on the foliage, dropping leaves, and stunted growth.

The plant might be wilting even though the soil feels adequately moist.

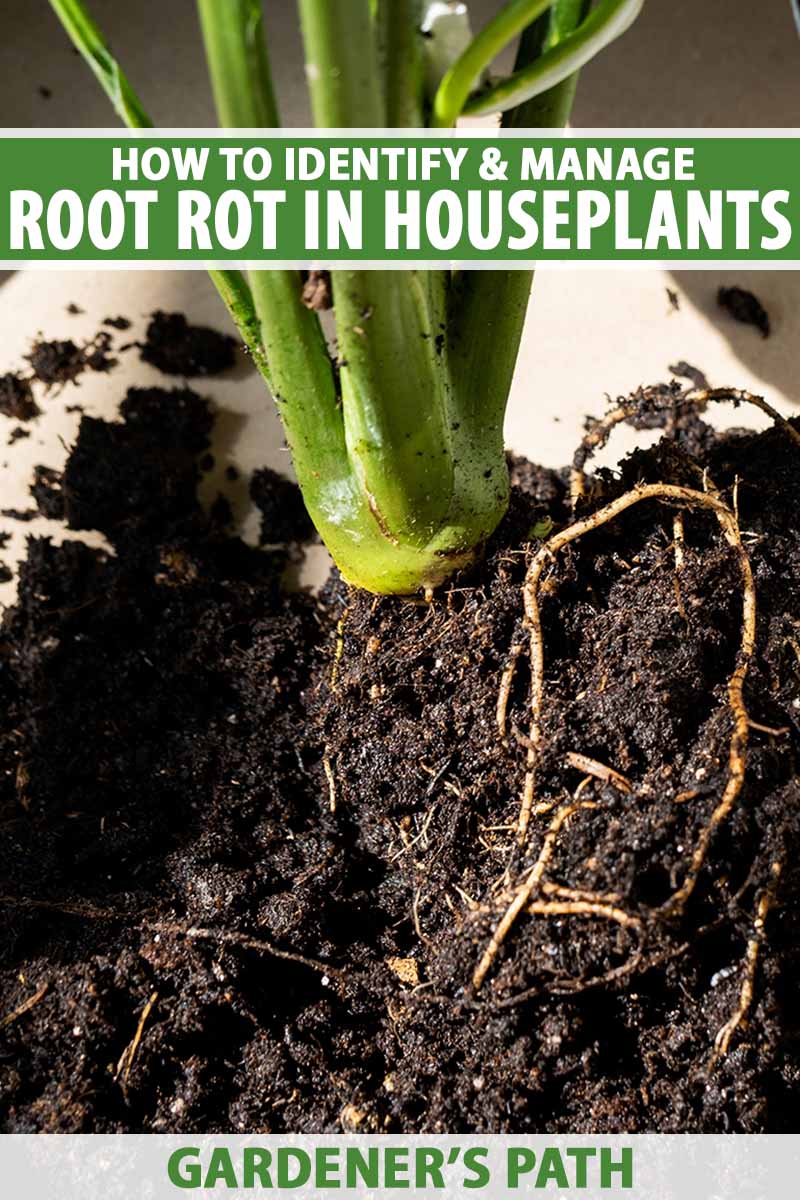

The best way to tell if the disease is present is to remove the houseplant from its container and inspect the roots.

You’ll generally see brown, black, dark, soggy roots. Some of the tissue might be healthy but there will be distinct evidence of rotting areas.

In the case of large, woodier plants like some palms and Ficus species, the outer layer of the roots – known as the epidermis – might slough off, leaving the pale interior exposed.

You might also notice a bad odor. If you’ve ever sniffed the old water in a vase that has been holding cut flowers, you know the smell.

Prevention

Root rot is almost always preventable. One of the easiest ways to avoid it is to be cautious about how much and how you water.

Avoid overwatering by testing the soil with your finger or a moisture meter before you water.

Don’t rely on a watering schedule, since every species is different and will take up moisture differently depending on the temperature, any breezes in your space, or the relative humidity in your home.

Make sure every container you use has drainage holes. You can place a container with drainage inside a decorative pot, but be sure to empty it out 30 minutes after watering. The same applies if you use any sort of water-catching saucer.

Use a well-draining potting soil suitable for the species that you’re growing, and don’t put a layer of rocks or broken pottery at the base of the pot. This actually makes the problem worse, not better.

When you water, be sure to apply the water to the soil, not on the leaves. Or use the bottom watering technique.

You can learn more about how to water houseplants in our guide.

Always use clean, fresh soil and wipe any tools or containers with a 10 percent bleach solution before pruning or potting up.

When you bring a new specimen home, isolate it for a week or two to make sure it doesn’t have any symptoms of disease to avoid spreading the pathogens to your other plants.

Finally, avoid stressing your plants. A stressed houseplant is more susceptible to pathogens present in the soil. Inappropriate light, drought, and pest problems can all cause stress.

Treatment

The first step in treatment is to remove the plant from the container and get rid of all the soil.

You might need to rinse the roots in a stream of lukewarm water, or it might just brush away if it isn’t oversaturated.

If you happen to catch a whiff of something unpleasant, sort of like the old water in a vase holding a bouquet of flowers, that’s a good indication of root rot.

When you have all the roots exposed, look them over carefully. If you find any that are black, soggy or broken, cut these off with a clean pair of scissors or clippers just a bit above where the damage ends. You want nothing left but clean, healthy roots.

Wipe the old container out with a 10 percent bleach solution.

Spray the roots with a fungicide formulated for root rot or a broad-spectrum fungicide. There are a lot of options on the market, but you don’t need to look for anything fancy. A classic choice is copper fungicide.

Another option is Actinovate AG, which contains the beneficial microbe Streptomyces lydicus WYEC 108.

This powerful fungicide is available at Arbico Organics in an 18-ounce bag.

That’s enough to treat a lot of plants repeatedly, so it’s ideal if you’re dealing with multiple specimens or just want to be sure you have something on hand.

After you have trimmed off all the rotten tissue and treated the roots, repot the specimen with fresh, clean potting soil. Continue to soak the soil with a fungicide according to the manufacturer’s directions until healthy new growth emerges.

Going forward, use a soil moisture meter and be especially careful not to overwater.

Resistant Species

If you really can’t stop overwatering your houseplants, either get an epiphytic species and mount it on wood or wire, or stick to growing air plants (Tillsandia spp.). It is almost impossible to overwater a mounted specimen!

In addition, there are a number of species that aren’t prone to this condition. These are some good choices:

Cast-Iron Plant

As their common name suggests, cast-iron plants (Aspidistra spp.) are tough. Really tough.

You’d have to absolutely drown this houseplant for a sustained period to kill a cast-iron plant.

The strap-like leaves come in various shades of green and can have beautiful variegation in the form of spots and or lines.

You can find cast-iron plants in one- and three-gallon containers available at Fast Growing Trees.

Learn more about cast-iron plants in our guide.

Cyperus

Cyperus species like umbrella sedge or papyrus plant (C. alternifolius) are extremely tolerant of wet feet.

They grow in swampy areas in the wild, so that should come as no surprise. If you’re a convicted overwaterer (raises hand), consider this palm-like species.

Fast Growing Trees carries this beautiful species if you’d like to bring one (or more) home.

Fuchsia

If you grow fuchsia (Fuchsia spp.) as houseplants, you’ll not only be treated to the gorgeous blossoms, but a specimen that will tolerate soggy conditions as well.

While they can technically suffer from root rot, you’d really have to make an effort.

Ficus

Many Ficus species are resistant to root rot, both from overwatering and from pathogens, but not all. Fiddle-leaf figs, for one, seem to be more prone than others in the genus.

My first experience with this disease was a fiddle-leaf fig that I overwatered for months before I realized what I’d done wrong.

It lost half of its leaves and needed some serious rehab, but it’s still with me and lovelier than ever after all these years.

But creeping figs (F. pumila), for example, won’t flinch at too much water.

Learn more about growing ficus plants in our guide.

Ivy

Ivy (Hedera helix) isn’t the easiest houseplant to grow, which is ironic given how prolific it is outdoors.

But of all the things that might make your ivy unhappy indoors, root rot probably won’t be one of them.

If you’d like to know more about how to grow ivy indoors, check out our guide.

There’s No Reason to Suffer With Root Rot

Root rot is one of the more common problems when growing houseplants, but that doesn’t mean it has to cause trouble in your indoor garden.

As I said, you can largely avoid root rot if you take a few precautions. Even if it this disease does become an issue, you can treat it if you catch it early enough and save your plants from certain doom.

Are you struggling with root rot? What symptoms are you seeing? Let us know in the comments section below.

And for more information about growing houseplants, check out these guides next: