Through the power of microbial action, inoculants help legumes convert nitrogen from the air into nitrogen they can use to grow and thrive.

That means using these beneficial microbes are key to ensuring a plentiful harvest!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Long before the creation of synthetic fertilizers, legume plants flourished thanks to the assistance of beneficial microbes living in the soil.

These microbial partners help legumes convert nitrogen from the atmosphere into a form the plants can use as nutrients.

And when organic gardeners and farmers take advantage of this mutualistic symbiotic relationship, we receive abundant harvests of legume crops containing more protein – without any synthetic nitrogen inputs!

Sound like a sweet deal? Now all you need to do is to pick the right bacteria for the job.

In this article you’ll learn which microbes to use for which crops, as well as how to apply them. Here’s a sneak peek at what we’ll cover:

Before we dig into these different options, let’s make sure we understand the purpose of applying inoculants, and look at why and when we should use microbial products when growing legumes.

Certain bacteria help legumes convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, a type of nitrogen biologically available to plants to help them grow – this process is called nitrogen fixation.

Legumes need nitrogen because without this plant nutrient, they can’t manufacture chlorophyll, protein or amino acids!

So bacteria help these plants access nitrogen – but what do the bacteria get in exchange?

In colonizing the roots of the legumes and creating nodules that fix nitrogen, the bacteria receive energy from the plants via their protective enclosures in the root tissue.

Some of the available nitrogen produced by this relationship is absorbed by the plant, some goes to neighboring plants, and some of it is only released into the soil after the plant dies.

That’s why legumes make such excellent companion plants and should be considered essential members of your garden or fruit tree guild!

Products containing these nitrogen-fixing microbes are called inoculants.

The types of legume inoculants proposed in this article are considered biofertilizers – they are alternatives to synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, making them appropriate for those adopting a more sustainable, organic approach to growing food.

Now that we understand that these relationships exist in nature, let’s look at why we have to give garden legumes a hand by adding microbes that come in a package.

When it comes to legumes, each member of this plant family has a specific microbial partner.

If the crop you wish to cultivate hasn’t been grown in the soil recently – or ever – those partner bacteria are likely missing, which will result in less vigorous plants and rather meager harvests.

Such would be the case for most raised beds, such as a newly built square foot garden.

And if you’re like me, you may be the type of gardener who likes to experiment with unusual fruit and vegetable crops. Why stick with tomatoes, cucumbers, and green beans, when you can also grow mouse melons, ground cherries, and yard long beans?

You may very well want to grow legume crops that have never been cultivated in your beds before. And when growing legumes in soils or growing mediums where they haven’t been grown before, an inoculant is necessary.

You might also want to apply these nitrogen fixing bacteria if the crops were grown in a plot previously, but yields were low.

To learn more about the benefits of using soil inoculants and microbes in the garden, read our article.

1. For Alfalfa and Clover

If you’re taking an organic approach to growing your own food, as part of your gardening strategy you might consider growing cover crops such as alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and clover ( Trifolium spp.).

These nitrogen fixers can serve as ground covers, helping with both pest control and erosion prevention.

Want to learn more about this practice? Read our article, cover cropping 101, to learn the basics.

Alfalfa and clover have their own nitrogen fixing bacteria partners – Sinorhizobium meliloti and Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifoli.

In addition to alfalfa and clover, the bacteria included in this mix also inoculate fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), a plant cultivated for its delicious seeds, which are used as a spice.

Alfalfa, Clover, and Fenugreek Powdered Inoculant

You can purchase packs of powdered inoculant designated for alfalfa, clover, and fenugreek in package sizes ranging from 0.25 ounces to five pounds from Mountain Valley Seed Company via True Leaf Market.

2. For Common Beans

Hoping for a bumper crop of haricots?

Common bean varieties should be treated with R. leguminosarum biovar phaseoli as a biofertilizer.

Inoculants containing this microbe are widely available, including in the multiple crop inoculant mix that you’ll learn about later in the article, so keep reading!

Be aware that not all crops called “beans” can partner with R. leguminosarum biovar phaseoli – this particular microbe creates relationships with only those in the Phaseolus genus.

Members of the Phaseolus genus include green beans, pintos, black beans, cranberry beans, kidney beans, and scarlet runners, among many other varieties.

Legumes with the “bean” moniker that aren’t included in this genus – and which therefore create partnerships with different microbes – include limas, favas, mung, soybeans, teparies, and garbanzos.

3. For Garbanzos

Speaking of garbanzos – hummus is an excellent snack standby, and you can take making it from scratch to a new level when you grow your own chickpeas.

Garbanzos (Cicer arietinum), also known as chickpeas, depend on a bacterium known as Mesorhizobium cicero for nitrogen fixing. This microbe is also sometimes referred to as Rhizobium cicero.

M. cicero serves as a microbial partner for all varieties of garbanzos.

Unfortunately inoculants containing this microbe are only available at this time to large scale farmers and not to the general public.

To find information about growing chickpeas without the proper inoculant, I reached out to Adaptive Seeds, a small seed company that sells chickpeas among other types of open-pollinated seeds, to ask them how they handle this tricky inoculation conundrum.

Co-founder Sarah Kleeger told me that they successfully used a different inoculant with their chickpea crop, and are still getting healthy roots with many nodules 10 years after applying it.

You’ll learn which inoculant they used later in the article, so keep reading!

4. For Peas, Vetch, and Lentils

Are you preparing to grow cool season legumes?

Garden peas (Pisum sativum) partner with their own type of nitrogen fixing bacteria, known as Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae.

Inoculants containing this microbe also prepare common vetch (Vicia sativa), favas (V. faba), hairy vetch (Vicia spp.), snow peas (P. sativum), lentils (V. lens), and the non-edible, ornamental sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus) for planting.

Pea, Vetch, and Lentil Inoculant

You can purchase this pea, vetch, and lentil inoculant in an assortment of sizes, ranging from 0.25 ounces to 10 ounces via True Leaf Market.

5. For Peanuts, Cowpeas, and Mung Beans

Some gardeners tend to travel off the beaten path, growing less common backyard garden crops like peanuts, cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata), and mung beans.

For all three of these, you’ll need a product that contains Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) nitrogen fixing bacteria.

For more abundant growth and more ample harvests, this type of nitrogen fixer will also prime adzukis (V. angularis), black-eyed peas (V. unguiculata), bush clover (Lespedeza spp.), limas (Phaseolus lunatus), partridge peas (Chamaecrista fasciculata), pigeon peas (Cajanus cajan), pink eyed purple hull peas (V. unguiculata), teparies (P. acutifolius), winged beans (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus), and yard long beans (V. unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis).

Peanut, Cowpea, and Mung Bean Inoculant

You can pick up a pack of peanut, cowpea, and mung inoculant in five-ounce bags, enough to treat 100 pounds of seed, from Garden Trends via Amazon.

6. For Soybeans

Are you growing edamame for tasty appetizers or to boost the protein content of your plant-powered stir fries?

Soybeans have their own nitrogen fixing bacteria, Bradyrhisobium japonicum.

Products that include these beneficial bacteria will prepare all types of soybeans for nitrogen fixation including varieties of Glycine max and G. soja.

Purchase soybean inoculant B. japonicum in pack sizes ranging from 0.25 ounces to 10 ounces, via True Leaf Market.

7. For Multiple Crops

If you’re growing several types of legumes in your garden, you may be able to choose a mix containing multiple types of bacteria instead of purchasing several different products.

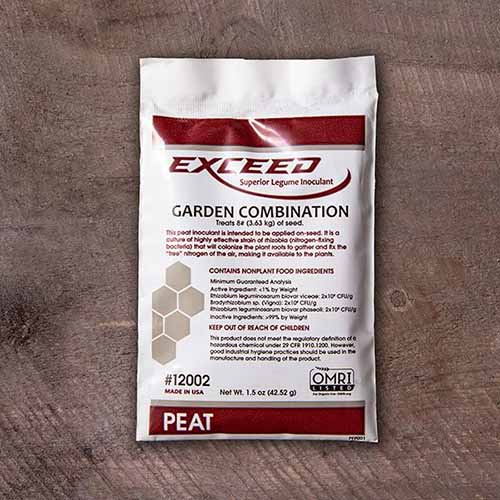

For instance, Exceed’s Garden Combination Inoculant contains the various bacteria needed to prepare the majority of the different legume crops we’ve encountered in this article.

The list of legume crops that will find microbial partners in this mix includes – are you ready?

- Adzukis

- Black eyed peas

- Bush clover

- Common beans

- Common vetch

- Cowpeas

- Favas

- Hairy vetch

- Garden Peas

- Lentils

- Limas

- Mung beans

- Partridge peas

- Pigeon peas

- Snow peas

- Sweet peas

- Peanuts

- Teparies

- Winged beans

- Yard long beans

Whew!

This product contains Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), and R. leguminosarum biovar phaseoli bacteria.

And according to the experience of growers at Adaptive Seeds as well as Bill Hageman, president of Peaceful Valley Farm and Garden Supply, though this mix does not include Mesorhizobium cicero, it should also work for chickpeas.

Exceed Garden Combination Inoculant

Exceed Garden Combination Inoculant in a 1.5 ounce bag, enough to treat eight pounds of seeds, is available for purchase from High Mowing Seeds.

How to Apply Legume Inoculants

Once you have chosen the right biofertilizers for your legume seeds, you may be wondering how exactly to apply them.

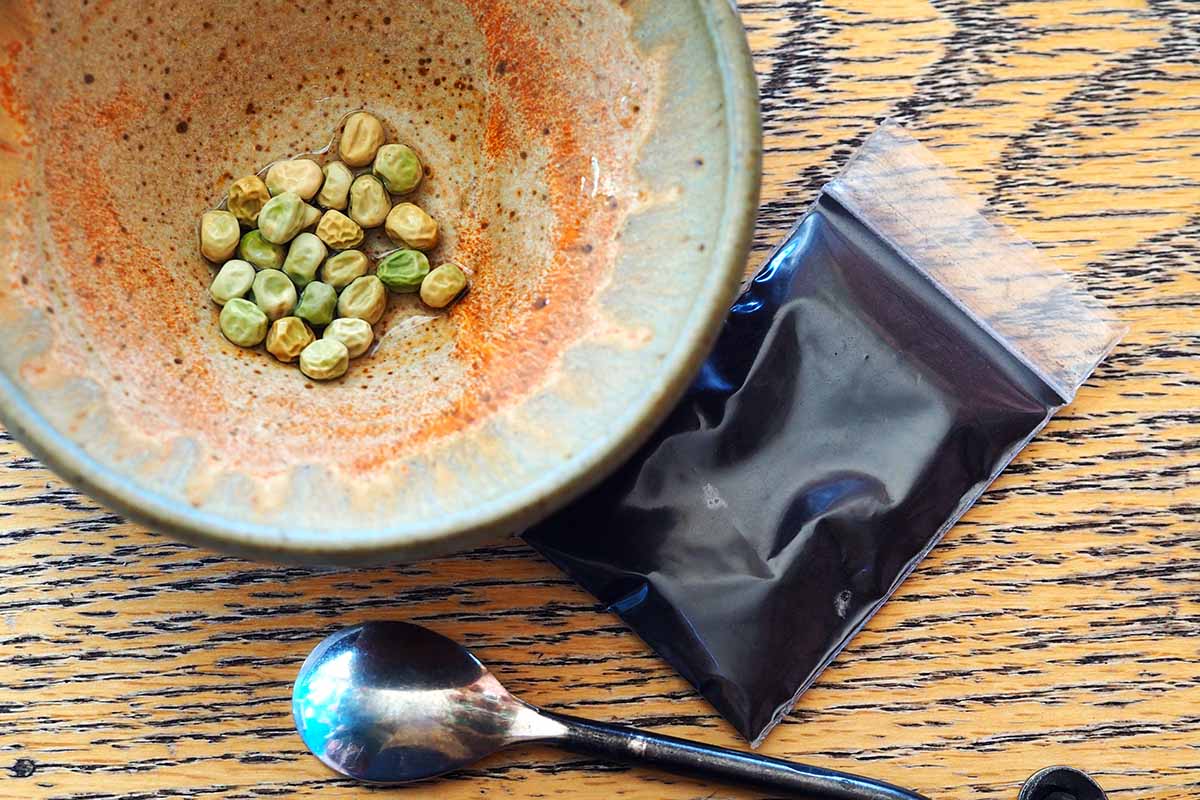

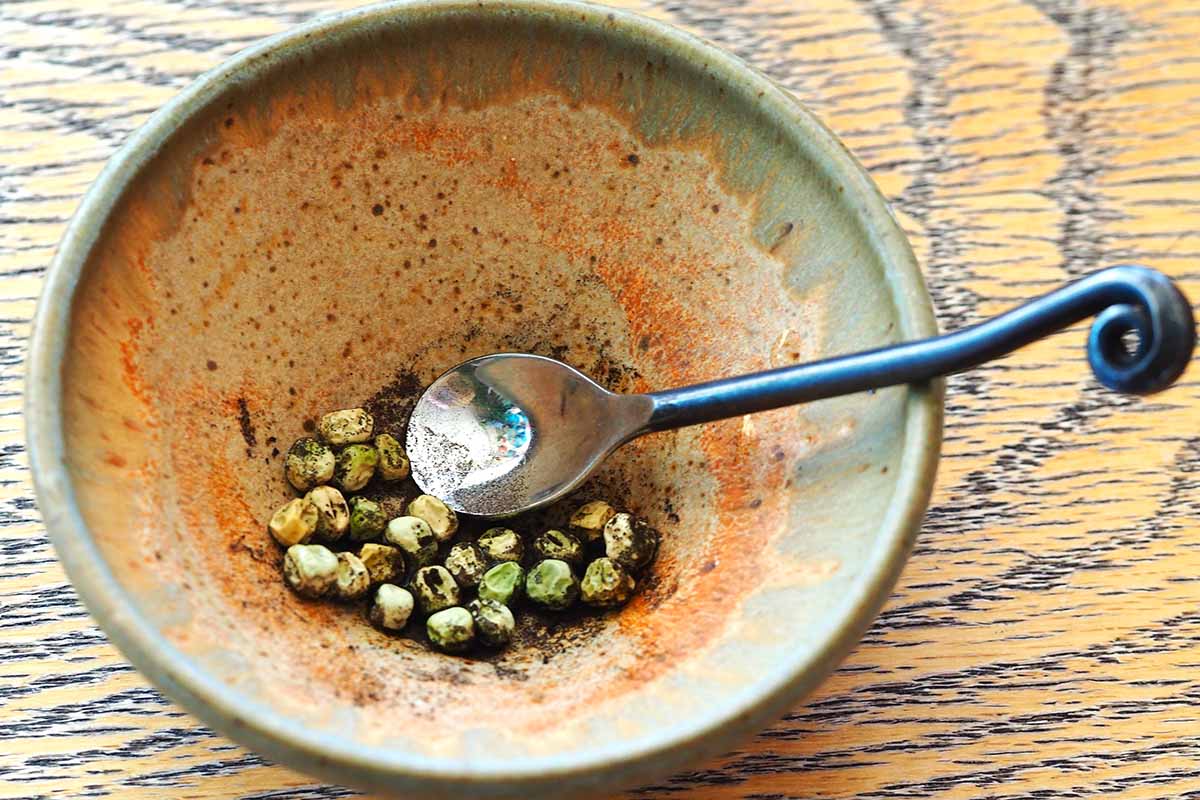

When you’re ready to sow, place the seeds you’re going to plant in a small bowl, and wet the seeds lightly.

Next sprinkle on a small amount of dry inoculant, which is the type most readily available to home gardeners. The water will help the powder stick to the seeds.

How much of this nitrogen fixing bacteria do you need to apply?

Check your package for directions. On my package of inoculant the directions say that one third of a teaspoon is enough to prepare one pound of pea seeds. Since I’m only planting 24 seeds, I only need a small sprinkle of the powder.

What if you already sowed your seeds and forgot to apply the inoculant?

Been there, done that. After all, legumes are an important part of the garden, but on seed sowing day, my mind is equally focused on the brassicas, herbs, lettuce varieties, and annual flowers I’m planting as well.

If you forgot to coat the seeds in the inoculant, you can still add the powder to the soil after planting – in fact, some farmers sprinkle legume inoculant into a furrow in the soil before or after seeding.

One more tip: be aware of the expiration date on your package of inoculant.

The organisms within are living and need to be used within the indicated time. Also be sure to store packages in a cool location out of direct sun exposure, such as a refrigerator.

Apply, Seed, and Grow

Hopefully, you now feel confident about using nitrogen fixing bacteria to help legume crops thrive in the garden!

Is this your first time applying these products to legume seeds? Let us know if any questions pop up while you’re sowing – we’ll be happy to help.

Ready to learn more about growing legumes? Check out these guides next: