Hippophae rhamnoides

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides), as its name implies, is a shrub with a thorny nature.

It has a number of other common names, including sea berry, sandthorn, and swallowthorn. But if you ask me the best moniker is “Siberian pineapple” – a reference to the plant’s cold hardiness and the flavor of its berries.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

These little orange berries – called sea berries – have made sea buckthorn popular thanks to their “superfruit” status.

The berries are commonly found in baked goods and cosmetic products across North America, but sea buckthorn is still not a familiar sight in home gardens.

In this guide we’ll discuss how to grow sea buckthorn. Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Is Sea Buckthorn?

Sea buckthorn is a medium to large shrub or small tree, growing between 13 to 20 feet tall with a spread of about 11 feet.

Its native territory spans the subpolar and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere – except for North America.

Often found naturally growing in subalpine, coastal, as well as desert regions, this versatile shrub is highly adaptable to many climates. It is very cold hardy, thriving in Zones 3 to 8.

Classification of the genus Hippophae is still evolving. Currently, there are six species in the genus. Of these, Hippophae rhamnoides is the most well-known and wide-ranging species. Other notable species include H. salicifolia and H. tibetana.

Sea buckthorn is a capable shrub that fixes its own nitrogen in the soil. Its quick growing root system and suckering habit makes it useful in preventing soil erosion and for use as a windbreak.

If you have a small garden, you can still plant sea buckthorn, but you’ll need to remove the suckers to prevent the plant from spreading. And if you want fruit, you’ll need two plants.

Sea buckthorn is dioecious, which means the plants are either male or female so you need one of each for successful pollination.

If you want more than one berry-producing shrub, aim for a ratio of one male for every four females in a small garden.

The flowers are pollinated by wind, so male and female shrubs should be planted about six to eight feet apart. If you want a dense hedge, aim to plant shrubs three feet apart.

Male and female blooms share certain characteristics – both are subtle, yellow flowers which open before the leaves appear in mid to late spring. They are not easily damaged by frost.

Your sea buckthorn will begin to flower once it’s four or five years old, at which time females will produce berries if pollination is successful.

The berries – which are usually orange although they can vary in color from yellow to red – ripen in late summer to fall. The taste is a unique melange of pineapple, orange, and lemon – quite tart with a hint of sweetness!

The berries grow very close together in bunches on thorny branches, making hand harvesting a formidable task. The reward? The fruits are highly nutritious and loaded with vitamins C and E, protein, carotene, fatty acids, and flavonoids.

The bright berries contrast beautifully against the shrub’s narrow, silver leaves.

Although sea buckthorn is deciduous, its long leaves – from three quarters to two and a half inches long – may stay on the bush through most of the winter, along with some berries.

True to its name, sea buckthorn sports one-and-a-quarter-inch sharp thorns along its branches. Fortunately, new cultivars are being developed with fewer and more delicate thorns.

Sea buckthorn belongs to the Elaeagnaceae, aka the oleaster family. Plants in the Elaeagnaceae family share a characteristic silver or reddish-brown luster which comes from hairs on the plant’s leaves, twigs, and buds.

You may recognize similarities between sea buckthorn and other members of the same family like silver buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea) – a North America native – which also has edible fruit and is often grown as a hedge.

Let’s take a look at why people first started cultivating this useful shrub.

Cultivation and History

Sea buckthorn has a long history of use spanning centuries. The genus name Hippophae comes from “hippo,” the Greek word for horse, and “phao,” which means “to brighten.”

This refers to its use by the ancient Greeks as horse fodder to promote shiny coats.

Although it is slowly becoming more commonplace in North America, its medicinal and nutritional qualities have been known in China, Tibet, and Mongolia for hundreds of years.

In the 1940’s scientists in Russia began studying the biologically active compounds in the fruit, leaves, and bark.

Sea buckthorn was brought to North America – more specifically the Canadian Prairies – from Russia in the 1930’s by Frank Skinner, a self-educated plant breeder and horticulturist.

He was looking for plants that could thrive in the harsh prairie climate. The introduction was a success and the shrub was used in shelter belts and to stabilize soil in the prairies.

But the potential for the berries as a food source, in North America at least, remained unexplored until Bill Schroeder, a Canadian researcher and plant collector, saw how they were being utilized by Russians in the 1980’s.

Russian astronauts were using sea berries as a food supplement in space. Realizing the high nutrient potential of the berries, Schroeder began breeding sea buckthorn for larger and sweeter fruit. This gave rise to a number of Canadian cultivars such as ‘Harvest Moon.’

Today, the sea buckthorn industry is well-developed in both Russia and China. They have planted large commercial orchards of H. rhamnoides for research and development of sea berry products.

Sea buckthorn is used in China and Russia in a number of medical applications such as to treat heart disease and heal burns and wounds.

In North America, you can find sea buckthorn oil, made from the seeds, in cosmetic products for rejuvenation of skin, treatment of eczema, and as a UV filter.

The global market for sea buckthorn is projected to steadily grow, so you can expect to see more products containing sea berries in the coming years.

Now that you’ve learned about some of the many uses for these exceptional shrubs, let’s discover how we can propagate them at home.

Sea Buckthorn Propagation

H. rhamnoides can be propagated in a few different ways. Let’s take a look at some methods:

From Seed

If you don’t mind waiting five years to know the sex of your plant, you can start sea buckthorn from seed. The upside of this method is that it’s simple – it just takes time.

You can either sow sea buckthorn seeds directly outdoors or start seeds indoors in winter. Seedlings started indoors have a higher chance of succeeding, but they require a bit more work.

For best results, start sea buckthorn seeds indoors in winter. To promote germination, the seeds must first be scarified. To do this, simply rub the seeds gently between two pieces of sandpaper.

Then, soak the seeds for 24 to 48 hours to soften the seed coat. Use room temperature water and change the water a few times.

After this, the seeds need to go through cold stratification for 90 days.

To cold stratify seeds, place them on paper towels moistened with water and keep them in a plastic bag in the refrigerator for three months. Check every once in a while to make sure the paper towel stays moist.

After this time, sow the seeds in individual pots that are up to 12 inches deep and two to four inches wide. Fill pots with a pre-moistened mix of peat and perlite. Cover the seeds with a quarter of an inch of the media and keep the pots in a spot with bright light.

Water the media so it remains moist but not wet. The seeds will germinate in about three weeks to one month. Grow them in pots for about three months until they can be transplanted outdoors in spring.

Sow sea buckthorn seeds outdoors in fall or spring. Scarify the seeds first as discussed above.

Prepare your planting area by smoothing out the soil with a rake. Sow seeds on the surface of the soil a few feet apart.

If you’re sowing seeds in fall, they will be cold-stratified naturally over the winter months.

Cover your planting bed with six inches of mulch to keep the soil warm – leaves or straw are good options. When the snow melts In the spring, take the mulch off of the planting bed. Water so the soil is moist but not drenched.

If you are sowing seeds in spring, you’ll need to cold-stratify them first. After sowing, keep the soil evenly moist but not waterlogged, and the seeds should germinate in about a week.

If you want to move your seedlings to another location, allow them to grow for one or two years before transplanting.

From Hardwood Cuttings

Unlike seeds, hardwood cuttings will be clones of the parent plant. So if you want to be sure that your new sea buckthorn is either a male or female, it’s best to propagate via cuttings. Remember, only female plants will produce fruit.

It’s relatively simple to propagate sea buckthorn from hardwood cuttings, and plants started this way may fruit earlier than those grown from seed.

When taking hardwood cuttings, it’s important to choose cuttings from the lower, lignified part of the shoot. This part will feel rigid and woody – unlike the softer, bendable ends of shoots.

Harvest your hardwood cuttings in early spring before the buds break, and the plant is still dormant. It’s a good idea to wear gloves to protect your hands from the thorns.

Ensure that your cutting tool is clean and sharp. Take six-inch cuttings from the last season’s growth – that woody, hardened part – making the cut just below a bud.

To root your hardwood cuttings, soak them in room temperature water with two or three buds above the water level for six days until the buds swell, making sure to change the water every day.

In about a week, you’ll see roots forming. When the roots are an inch long, you can plant the cuttings in pots and keep them indoors in a bright, sunny location.

Your planting tray or pot should be six inches deep. Use half perlite, half vermiculite for your propagation medium.

Stick cuttings about three inches deep into the rooting medium and space them three inches apart. Water regularly so the media is moist but not drenched.

After around two months, check to see if the cuttings are well-rooted by gently lifting the cutting out with a tool like a pencil or dowel. Once they are rooted, you can transplant them outdoors.

From Softwood Cuttings

Propagating from softwood cuttings has an even higher rate of success than hardwood cuttings.

Unlike hardwood cuttings which are already woody, softwood cuttings should be more flexible and less rigid. Take your softwood cuttings in late spring or early summer.

Prepare propagation pots that are six inches deep with holes for drainage. Fill them with a pre-moistened mix of half perlite and half vermiculite as a rooting medium.

With clean, sharp pruners or a knife, and your gloves on, take four- to six-inch softwood cuttings from the tips of healthy shoots. Remove the leaves from the bottom two inches of the cutting, leaving two to four leaves at the top.

Apply rooting hormone to the bottom inch or so and stick them into the medium with two nodes buried. Keep the pots indoors in a bright location such as a sunny windowsill.

Water the media regularly but don’t allow it to become waterlogged. Keep softwood cuttings in the media for one to two months before transplanting.

Check that they’re fully rooted by carefully lifting the cutting out of the pot with a pencil or dowel. When they are fully rooted, transplant them into the garden.

Transplanting

The best time to transplant your new potted sea buckthorn plant is in early spring. Cuttings can be transplanted when they have developed sufficient roots.

Dig a hole that is slightly deeper and wider than the original container. Ensure the soil in the hole is free of rocks and debris.

Remove the plant from its container and inspect it. If the plant is rootbound you’ll need to make shallow, vertical cuts in the ball of soil. Also cut two crossing lines on the bottom of the root ball.

Place the plant into the soil so the top of the root ball is level with the surface of the soil. Backfill with soil and pat it down. Water in well.

Keep your new plantings evenly moist but not waterlogged until they are established.

How to Grow Sea Buckthorn

There’s no way around it – sea buckthorn needs full sun to produce those wonderful berries. Although it can survive in partial shade, it will not thrive.

Take it from someone who has tried to coax fruit out of a sea buckthorn planted in less than ideal growing conditions – it won’t work! After just three years of growing in partially shady conditions, my sea buckthorn was already suffering so much that it didn’t make sense to keep it.

Another requirement is well-draining, loamy soil with a pH of 5.5 to 7.5. Waterlogged soils are unacceptable for sea buckthorn, but the plant can tolerate saline soils.

Don’t allow weeds to invade the area near your sea buckthorn as it’s becoming established. Your shrub will benefit from mulching with organic matter like compost.

Mulching helps the soil to retain moisture and has the added benefit of suppressing weeds.

Place two to three inches of mulch around your shrub all the way to the dripline – keeping the mulch four inches away from the trunk.

If you take the time to care for your shrub, your sea buckthorn should provide you with berries for 20 years or more!

Once it’s fully established after one to two years, sea buckthorn is drought tolerant.

But if you want to maximize fruit production, you’ll need to provide supplemental irrigation, especially during dry spells. Watering with drip or trickle irrigation is ideal.

You’ll know it’s time to water when the top six inches of soil are dry. To check, use a shovel or a similar tool to dig into the top six inches of soil. If it feels dry instead of moist at this level, it’s time to water.

Watering deeply but infrequently is better than more frequent, shallow waterings.

Avoid watering solely around the trunk of your shrub as this can actually cause decay. Instead, aim to water the entire surface area of the roots out to the drip line.

Fertilizing

This capable plant has a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria so it doesn’t require additional nitrogen and may even be harmed by its application.

If you notice new leaves that are smaller than usual, or older leaves that are changing color to a dark blue-green, your shrub may be deficient in phosphorus.

In this case, try adding a fertilizer with only mineralized phosphorus – not an all purpose fertilizer which will include nitrogen as well – such as this one from Arbico Organics.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun.

- Water regularly while shrubs are becoming established.

- Mulch to suppress weeds.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning is a necessary task when growing sea buckthorn. Make sure to wear gloves that will protect your hands and arms from the thorns.

As these plants can be quite dense, thinning them out allows sunlight to penetrate and improves airflow. It also encourages fruit to develop on the interior branches.

In general, female plants should be pruned to maintain a compact shape that will make harvesting easier, while male plants should be left to grow tall to aid in wind pollination.

Your overall aim when pruning sea buckthorn should be to keep the main stem and three or four branches that grow from the main stem – these will be where most of the berries develop.

Prune off any shoots or suckers that come up from the ground, as well as any side shoots. Also cut off any branches that droop at their ends – these will shade the inside branches.

Sea buckthorn should be pruned the first year of planting, in late winter before the buds begin to break. As your shrub ages, aim to prune any wood that is six years old or more.

If allowed to sucker, sea buckthorn will form dense thickets which is good if you want to grow a windbreak or hedge, but not so good if you want one neat shrub.

To prevent suckers from getting out of hand, you’ll need to contain them by mowing, or simply pulling or pruning them out.

Sea Buckthorn Cultivars to Select

Sea buckthorn is normally available at your local plant nursery or garden center. There are also a few notable cultivars.

Chuiskaya

‘Chuiskaya’ or ‘Chuyskaya’ is an older European female variety that is one of the most commonly planted in Siberia so you know it’s extremely cold-hardy!

With minimal thorns, this variety is simple to hand harvest. It will grow up to five feet tall and is hardy to Zone 3.

Harvest Moon

‘Harvest Moon’ is a Canadian female cultivar that produces large, red-orange berries and a hefty harvest.

It has fewer thorns than the species plant and is easy to harvest by hand. It’s hardy to Zone 3 and grows up to 10 feet tall.

Lord

A popular male cultivar is ‘Lord,’ a Russian variety that contains few thorns and grows to 10 to 12 feet tall.

It’s hardy to Zone 3 and boasts beautiful foliage and pretty flowers in spring which don’t bear fruit. A male is needed as a pollenizer for a female plant.

Managing Pests and Disease

Fortunately for us, the list of insects and diseases which affect sea buckthorn is mercifully short and not usually a cause for serious concern.

Herbivores are another story, however, as they may at times cause quite a bit of damage. Here’s what to watch out for:

Herbivores

There are a number of critters that may enjoy your sea buckthorn as much as you do. Among them are birds, deer, rabbits, and rodents.

Deer

Deer will flock to sea buckthorn given the chance. They’ll happily feed on foliage and branches as well as any fruit.

They can also trample young plantings. Giving deer an alternative food source or using repellents may lessen the problem.

Learn more about dealing with deer in our guide.

Rabbits and Rodents

Rabbits and rodents like field mice, meadow voles, and pocket gophers will cause the most damage on young shrubs, established plants are usually safe.

Use wire or mesh to prevent rabbits from chewing new buds and bark. Mice will usually do their damage in winter. Pocket gophers tend to eat sea buckthorn roots.

You can prevent these critters from harming your shrubs by keeping any tall grass around the sea buckthorn mowed. If they become a big problem, you can trap these rodents to control their populations.

Insects

There are only a few pests that will go after your sea buckthorn – these include Japanese beetles and aphids.

Aphids

These tiny pests are just an eighth of an inch long with soft, pear-shaped bodies that can be green, yellow, black, brown, or red.

It’s uncommon to find just one or two aphids – where there’s one there will usually be many! They congregate on leaves or stems and they don’t move much when you disturb them.

As they go about their business of sap-sucking, they expel a sticky honeydew on the plant leaves which can promote sooty mold that suppresses the plant’s ability to photosynthesize.

The good news is that moderate numbers of aphids won’t damage your sea buckthorn. The bad news is that large infestations can cause damage and even transmit plant viruses – and these little suckers reproduce quickly.

You’ll know the aphid infestation is large if you notice yellow leaves and stunted shoots on your shrub.

So what can you do? Fortunately, there are quite a few natural and effective controls.

Monitor your plants, especially new growth, for the presence of aphids so you can prevent a big population from forming.

Another preventative measure is to plant flowers that attract natural predators like lacewings, hover flies, lady beetles, and parasitic wasps which feed on aphid colonies.

Some options are Queen Anne’s lace, yarrow, or sweet alyssum. I always have tons of interesting looking beneficial insects visit my lovage every year!

Where aphids are present, spray them with a strong stream of water from your garden hose to wash them off the plant.

Personally, I don’t mind squishing them with my gardening gloves on! Another option is to prune out entire branches that are heavily infested.

If you want to use chemicals, opt for an insecticidal soap with a low risk to beneficial insects such as Bonide Insecticidal Soap available from Arbico Organics.

You can learn more about dealing with aphids in our guide.

Japanese Beetles

The pesky Japanese beetle has become an increasing nuisance in North America in recent years and sea buckthorn is on its “to eat” list.

This metallic brown and green beetle will munch on the foliage, leaving large holes. These leaves will eventually turn brown and fall from the plant.

Managing Japanese beetle populations must be approached differently depending on the time of year and stage of the insect’s life.

The adults feed on the leaves, so once the beetles start flying in the middle of summer, you’ll need to take control.

Removing beetles by hand is a tedious – and slightly gross! – but effective method. Put the beetles you pick in a bucket of soapy water so they don’t fly away.

Try to do this as soon as you see the beetles and don’t give up – daily removal will help you keep on top of them.

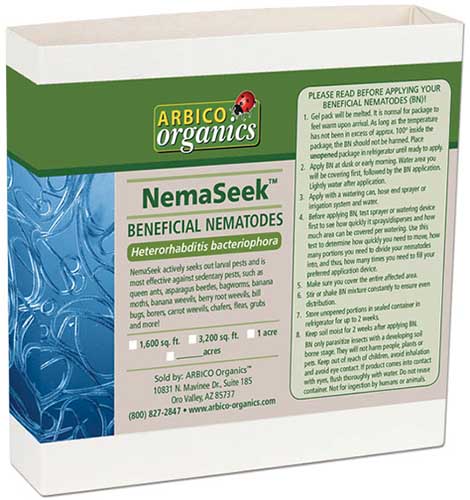

Beneficial nematodes can be used in late summer or early fall to manage Japanese beetle populations for the next year. Nematodes are a type of roundworm present in the soil.

The nematodes enter the bodies of the larvae and kill them by emitting a bacterium. These nematodes are great because they only attack insect larvae and are nontoxic to other animals, plants, and humans.

There are a number of options such as NemaSeek, available from Arbico Organics.

It’s important to note that while nematodes will manage grubs in your soil, they won’t prevent beetles from migrating to your sea buckthorn from elsewhere.

You can learn more about dealing with Japanese beetles in our guide.

Disease

Sea buckthorn is a robust shrub that isn’t affected by many diseases. That being said, verticillium wilt and fusarium wilt can sometimes be an issue.

Wilts

Verticillium wilt caused by Verticillium albo-atrum and Verticillium dahliae, or fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium spp. cause a variety of symptoms including yellowing, wilting leaves, and dieback.

The disease shows up when shrubs are five to eight years old and it only takes one or two growing seasons to finish off its victim.

Since the pathogens are soilborne, you should destroy affected plants and avoid planting sea buckthorn in the same location for at least three to five years.

Harvesting

Sea buckthorn will produce an abundant annual harvest in the late summer to fall, depending on your growing zone.

Different cultivars produce berries of varying colours. Some are yellow when ripe – others orange or red. Try to harvest fruit as soon as possible because the skin becomes thinner as it ripens.

Since most sea buckthorn plants have at least some thorns, harvesting the fruit can be tricky.

The other factor which can make it difficult is that the berries do not have an abscission layer – a layer of cells that causes the fruit to detach when it’s ready – so even when they’re ripe, they don’t detach easily from the stem.

There are a few ways to go about harvesting the berries. If you want to harvest by hand, take hold of a berry, twist it around, and pull it off.

I found harvesting berries one at a time was easier than trying to strip a whole bunch off at once because the fruit has thin skin and may squish easily – but of course, this takes longer.

I prefer to harvest sea berries with my bare hands and try to avoid the thorns. If you want to play it safe, wear gloves to avoid being scratched, but you may find thin gloves make the task easier than thicker gloves.

Another common way to harvest is by cutting and freezing fruiting branches. This is quite easy to do since sea berries grow tightly bunched together on the branches.

When the berries are ripe, cut off branches with fruit and put them in your freezer. Once the fruit has frozen, remove the berries by knocking them off the branches.

The catch with this method is that you should only cut a third of the fruiting branches or you risk damaging the plant and a much smaller harvest next year.

Sea buckthorn leaves are also full of antioxidants and vitamins. You can harvest the leaves any time of year and dry them to steep for tea.

If you want to harvest a big batch of leaves at once, it’s a good idea to use the male plants since they don’t have to put energy into fruit production. You can also harvest the leaves from branches during pruning.

Preserving

Fresh sea berries don’t have a long shelf life. You should refrigerate them as soon as possible after harvest and use them in one or two days, or freeze them to use later.

To freeze, place your berries on a baking tray in a single layer. Freeze them for a few hours and then store them in a sealed plastic bag or airtight container.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Sea berries truly are superfruits – they are rich in vitamins C, E, and K as well as carotenes, flavonoids, amino acids, and antioxidants.

And although the berries taste quite sour on their own, they can be transformed into jelly, jam, sauce, and juice.

One of the first ways I was introduced to the unique citrusy pineapple taste of sea berries was through a delectable cocktail made with fresh juice.

In fact, I often enjoy a non-alcoholic version of this made by simply boiling the frozen berries for 10 minutes, straining the seeds and pulp, and adding bubbly water for a refreshing spritzer.

If you want to try making your own dessert, you can find a sea buckthorn mousse recipe from our sister site, Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous shrub or small tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | Yellow/silvery green |

| Native to: | China, Russia, Mongolia, parts of Northern Europe | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-8 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Fall (berries) | Tolerance: | Drought once established, saline soils, wind, poor soil |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Type: | Sandy loam |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.5 |

| Spacing: | 5-6.5 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Slightly deeper than nursery container (transplants), quarter inch (seeds) | Uses: | Borders, edible harvest, erosion control, defensive planting, windbreak |

| Height: | 6.5-13 feet | Family: | Elaeagnaceae |

| Spread: | 8-12 feet | Genus: | Hippophae |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, deer, Japanese beetles, rabbits, rodents; Fusarium wilt, verticillium wilt | Species: | Rhamnoides |

A Fruit That Wears Many Hats

Sea buckthorn is an incredibly versatile plant – it offers a generous harvest of super healthy berries, it boasts beautiful foliage almost year-round, and its thorny nature allows it to be used as a defensive planting.

Sea buckthorn has something for everyone – it’s extremely cold-hardy, not bothered by too many diseases or pests, and quite low maintenance. Why not try growing one in your garden?

If you have experience growing sea buckthorn, share it with us in the comments below.

And for more information about growing shrubs in your garden, read these guides next: