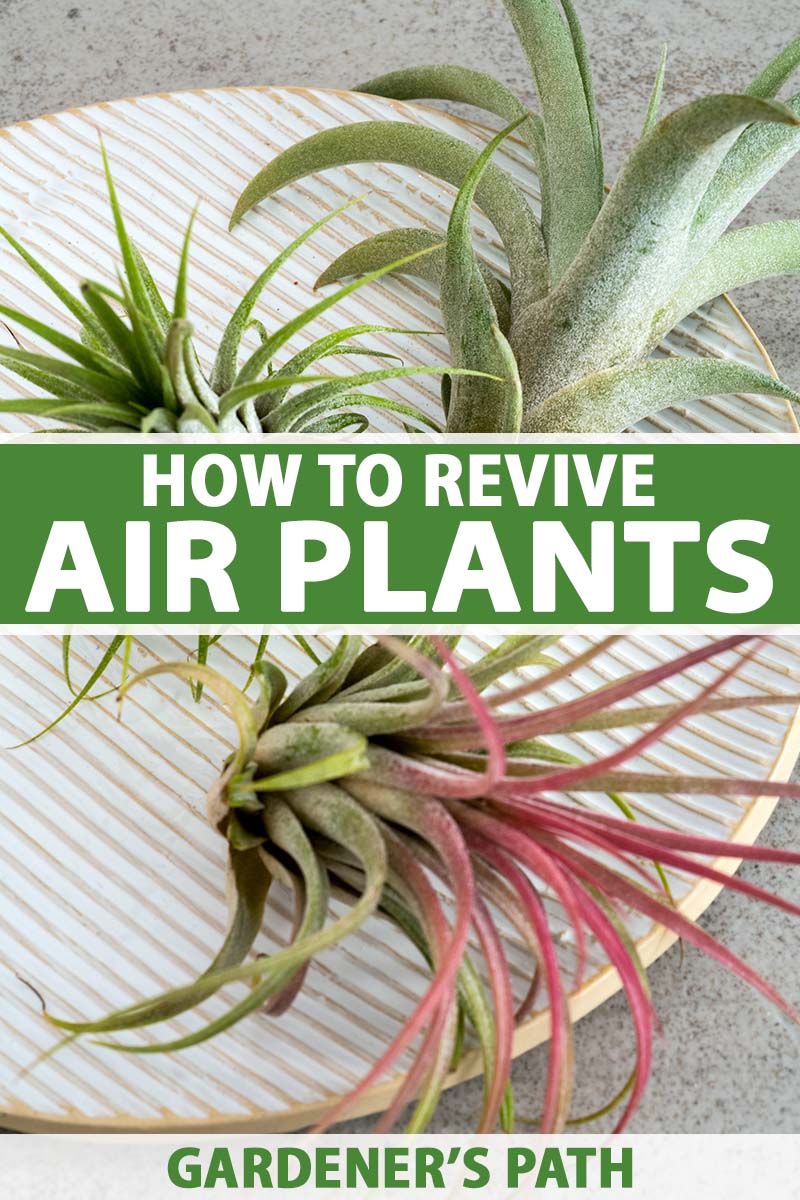

Tillandsia air plants are unique for their ability to grow without soil, relying on ample air circulation, moisture, and sunlight to sustain them.

They are fun houseplants because you can perch them anywhere, from bookshelves to picture frames, for eye-catching living art displays.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Unfortunately, because they don’t grow in a pot of soil, it’s easy to forget to water them. And conversely, because we have no soil to gauge moisture levels, it’s just as easy to oversaturate them.

Our guide to growing tillandsia air plants discusses all you need to know to grow your own.

This article zeroes in on rescuing air plants suffering from dehydration or oversaturation.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Let’s start with a review of growing essentials.

Tillandsia Air Plant Basics

The Tillandsia genus is in the Bromeliaceae family of flora, which includes bromeliads and pineapples.

There are two types: xeric and mesic.

Both live without soil, nestling in tree bark and on other natural elements, where they absorb nutrients from moisture and organic debris via rain and wind.

Xeric varieties grow in bright sunlight in semi-arid desert climes. They have prominent, hair-like “trichomes” that draw water and nutrients into their fleshy foliage, enabling them to withstand low moisture conditions. These trichomes give xeric varieties a dull gray cast.

Mesic species originate in rainforest canopies, enjoying consistent moisture and dappled sunlight. Their smaller trichomes are less prominent, so their leaves are brighter.

As houseplants, both types perform well in bright, indirect sunlight with ample air circulation. Xeric species do not require humidity, while mesic types prefer high humidity above 50 percent.

The ideal temperature range for both types to thrive is 65 to 85°F during the day and 50 to 65°F at night.

An air plant’s life cycle culminates with blooming, after which an offset or “pup” grows and the parent dies.

When providing tillandsia with moisture, allow the water to sit out in an open jug with the cap off overnight to evaporate harsh chemicals, like chlorine, a common addition to municipal tap water.

Chemicals may have adverse effects on these plants, such as foliar discoloration, and dehydration from salt accumulation that causes poor nutrient uptake.

Keep a prepared jug on hand for use as needed. Once a month, you can include liquid houseplant or bromeliad fertilizer diluted to a quarter strength.

Mist xeric types every other week, shake off the excess droplets, and allow them to dry for up to four hours, especially if you keep them in a partially enclosed container, like a terrarium.

For mesic species, mist or rinse in water twice a week or soak weekly for 20 to 30 minutes. Shake off the excess droplets and allow them to dry for up to four hours.

Take special care to dry thoroughly in an inverted position, or water may accumulate in the crown, where the leaves come together, and make them susceptible to rotting.

Inadequate light can cause conditions similar to both under- and overwatering, so supply bright indirect light daily.

With good basic care, flora is suitably hydrated and displays no under- or oversaturation symptoms. However, sometimes we forget to water, are too generous, or don’t thoroughly dry the foliage, and that’s when we need to jump into revival mode.

Here’s how!

Dehydration Symptoms and Rejuvenation

First, have a good look at your air plants. Is the foliage dull? Are the leaves green, but the tips appear brown and brittle? Is the foliage curling backward or dropping off?

If so, your plant may spiral downward and eventually die of thirst from lack of water, and fast action is required.

Start your revival efforts by removing any dead foliage using sanitized scissors. Clip off entire leaves or just the tips as needed. For the smallest species, use small nail scissors.

Then submerge the plant entirely in water, leaving it overnight.

After soaking overnight, remove the plant and shake off the excess water.

Dry inverted on paper towels.

Return to the permanent location once the leaves are completely dry.

The flip side of dehydration is oversaturation, which is harder to alleviate and can rapidly escalate to rotting.

Some species have a dark brownish base independent of the darkness the leaves typically display when they are oversaturated. Know your species and avoid underwatering types with a dark base, like Tillandsia tricolor.

Signs of oversaturation include swollen foliage, the detaching of leaves, mushiness, yellowing, and blackening.

If you notice these signs, act swiftly, using sanitized scissors or your fingers to remove mushy foliage.

Dry the remaining portions with paper towels or a hair dryer set on low, and place the plant in bright, indirect sunlight.

Allow time for recovery before watering again. When to do so is a judgment call and varies with the extent of oversaturation. Skipping one week’s watering is likely suitable.

Additional Factors

When flora is overcrowded, the moisture may not evaporate sufficiently and the plants may remain wet after misting or soaking, becoming oversaturated and prone to fungal infection. Inadequate sunlight may also contribute to foliage remaining wet.

Also, intense direct sunlight may scorch foliage, turning it brown and causing leaf drop as though the plant is underwatered. Dry plants are prone to infestation from pests like mealybugs and scale.

Specimens plagued by pests or diseases are likely to respond to revival methods better with an application of a product like organic neem oil, an insecticide and fungicide used to combat a host of houseplant issues. It has a strong garlicky smell, so use it outdoors when possible.

Finally, during the aging process, leaves naturally shed, so if this is the only “symptom,” you likely do not have a moisture stress issue.

A Second Chance

Reviving moisture-stressed tillandsia air plants is possible, provided there is still unaffected, healthy growth.

If dehydration crisps all the foliage, or oversaturation turns every leaf to mush, there will likely be no chance of recovery.

With bright, indirect sunlight, ample airflow, and appropriate moisture, air plants have the best chance of survival as houseplants. Revival measures offer home gardeners a second chance at giving them their best indoor life.

Do you grow tillandsia air plants? Have you dealt with moisture stress and revival? Please tell us about your experience in the comments section below.

If you found this article helpful and want to read more about tillandsia air plants and other epiphytes, we recommend the following guides next: