IT WAS ALMOST two years ago to the day when Joan Strassmann last visited me on the podcast, right around the time her book “Slow Birding” was released.

Now, as then, I’ve seen what are pretty much my last migrant warblers of the year move through the garden, and I’m wondering how long I get to look at the garden’s masses of winterberry holly fruit before the robins and cedar waxwings have at them, and whether the black bears will let me put up the bird feeders as early as Thanksgiving this year or not without a run-in.

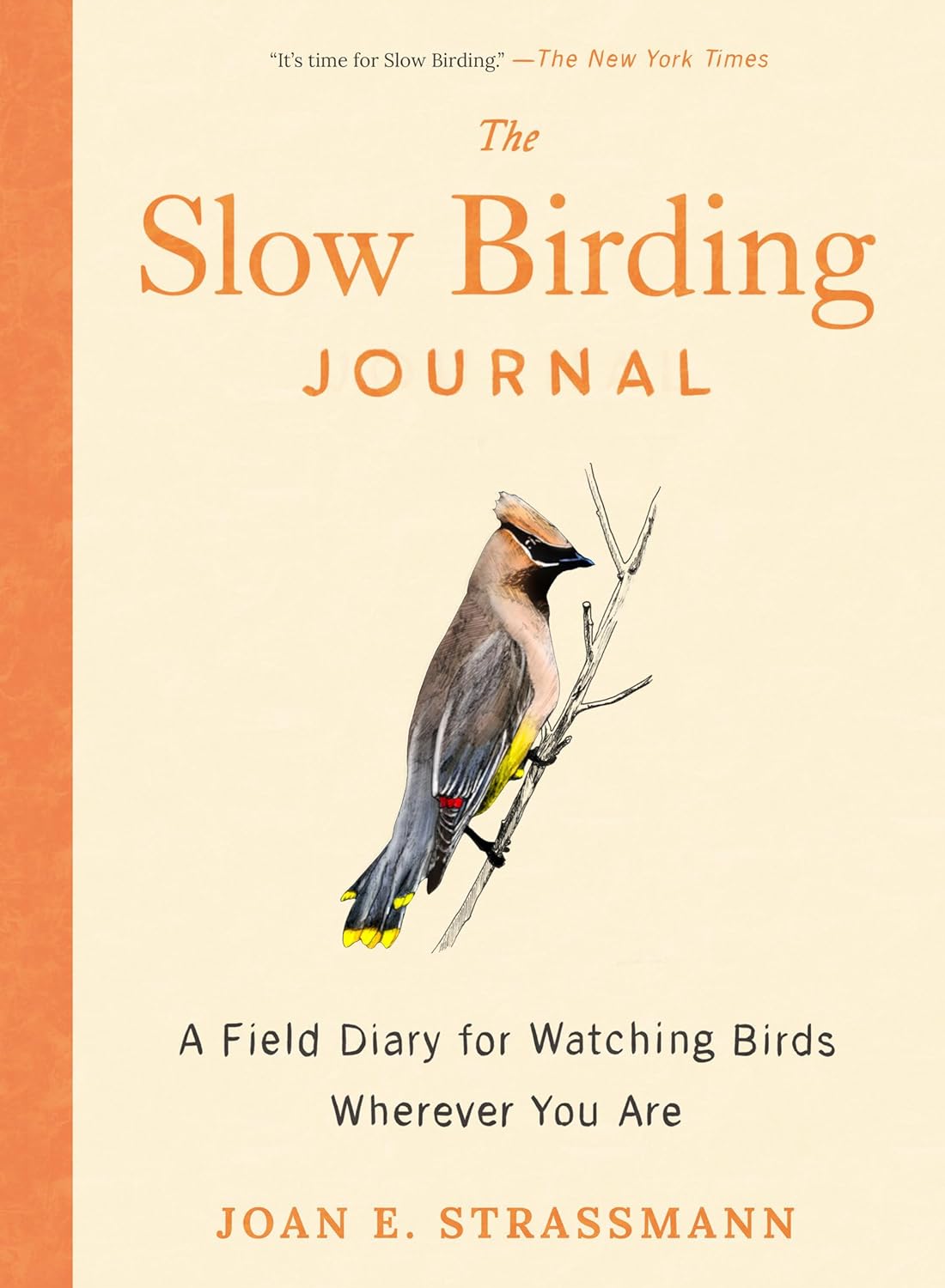

Joan Strassmann is back to talk about her newest book, a companion to the first, called “The Slow Birding Journal: A Field Guide For Watching Birds Wherever You Are” (affiliate link). Joan is an animal behaviorist and professor of biology at Washington University in St. Louis. As the titles of both books encourage us to do, Joan advocates for really emphasizing the “watching” in bird watching, not just ticking off names on a list, but trying to see what they’re doing and what inferences you can draw from their behaviors.

Plus: Enter to win a copy of the new book by commenting on the box near the bottom of the page.

Read along as you listen to the Oct. 14, 2024 edition of my public-radio show and podcast using the player below. You can subscribe to all future editions on Apple Podcasts (iTunes) or Spotify (and browse my archive of podcasts here).

slow birding, with joan strassmann

slow birding, with joan strassmann

Margaret Roach: I’ve been having fun with the new book. And how are your home birds, as I recall that you refer to them, the birds that are sort of right around us that you encourage us to get to know a little better?

Joan Strassmann: Oh, they’re just fine. It’s just so much fun to see them. I was in Northern Michigan, at my summer cottage for quite a while, so when I got back to St. Louis, I just, I guess, especially loved hearing the Carolina wren singing away, which we don’t have in Northern Michigan. And then of course the cardinals and the blue jays, and I even got to see a Cooper’s hawk. So yes, the birds are wonderful.

Margaret: Yeah. And it’s been the changing of the guard lately around here, and I guess everywhere, with the migration and so forth. Like for me, the white-throated sparrows are showing themselves in larger numbers, kind of picking through the garden, looking for seeds and stuff. And like you said, the Carolina wren, who’s always around, but is really making itself known, clings to the… It’s funny, it clings to the screens on my office window, so I’m looking right at the bird [laughter].

Joan: No, that’s nice.

Margaret: It’s cute. And I had a bunch of… Just a couple the last days of September, probably the last warblers I’ll see, the black-throated blue warblers were here visiting, eating fruit, and very, very nice for a couple of days, a bunch of them. Yeah. So, fall. It’s an interesting time.

Joan: Yeah. It’s the time to cherish your last chimney swift. Every time I hear them, I wonder, is this the last day? I’m still waiting for the white-throated sparrows and the juncos, of course. But yes, the changes make slow birding extra special, because there is change, even though it’s on an annual cycle.

Margaret: And even birds who are here year round, or here, wherever we are, with us year round, their behaviors change. Their vocalizations change. There are things that are different. So to listen more carefully and to watch more carefully in all the seasons, I think, is the kind of thing that you advocate. Yeah.

Joan: Yeah. I mean, it’s just wonderful to see how they managed. I know on one really cold day a couple of years ago, a robin actually came to my suet feeder, and generally robins never go to feeders, but I guess that robin really wanted some suet.

Margaret: [Laughter.] It heard that it was tasty. That’s funny. That’s funny.

So the new book, “The Slow Birding Journal,” it’s like a companion to the first, and it has profiles of some familiar birds, birds that were in the first book, I believe. But this one, the journal, is even more interactive in a way. It sort of suggests activities. Well, the other one did, too, but this is… Well, it has space for us to actually write down our observations. It’s a journal, as the title suggests. So tell us your intention with this one.

Joan: So sometimes it’s a little bit overwhelming to just take a blank book out in the field and try to find something to write about. So I thought, wouldn’t it be fun to have a book that just sort of helped guide you a little bit, and wasn’t too onerous or huge, but just had simple exercises that you could do and write about, right in the book? So the pages have those tiny little dots, which are my favorite kind of guides, because you can use them either to draw or to write, and they’re not too intrusive. And the idea is to just go out there and watch the birds. And there are prompts for the birds, and there’s also very freeform prompts to just help you watch the birds.

And I mean, this is something Amy Tan did in her marvelous book, which was publishing her journal and her incredible drawings, and maybe this one can help you send one on the way towards that sort of thing. So as soon as I get my hands on an actual copy of it, I plan to go out there and do it myself for every bird, because I’ve thought about it, but… Anyway, so I’m really looking forward to this one.

Margaret: Yeah, there were fun… There was one activity that I liked, I think it was called the home activity, up sort of near the front of the book, where you said to get a piece of string, and tie it so that you could make a circle with it, and put the circle down… This wasn’t a bird thing, exactly. It was a plant thing. Put it down on the ground and see what was within the circle, and then move the string into a circle in another spot and see what was there, kind of looking at the diversity of what was within even just a small circle of an area in your own yard, in two different places or three different places or four different places.

Joan: Yeah. That’s one of my very favorite activities, and it’s something I’ve done when I’ve done science activities with children. It’s something I’ve done with university students. And again, it’s just a way of framing nature in a little chunk that might be manageable. And if you just say, “What grows on the path, and what grows in the field,” that’s so general, but if you just put that circle down and let you focus just on what’s right there, it can be really powerful.

You could also imagine… There’s another exercise in that section, which is letting your window be the frame, and just looking exactly what it is that you see. So I really like framing activities that help you turn off all of the distractions, not the kinds we normally think of, but even just the distractions of a meadow full of plants, and just say, “O.K,, for right now, my universe is in this circle, and I’m going to watch and see what’s right there.”

Margaret: It’s interesting. I’ve been experimenting, I have a kind of a meadow above my house, and it’s been getting bigger each year, but I’ve also been experimenting with un-mowing, as I call it, some other spots that aren’t that far away from that meadow, but a bunch of different ones, like four or five other spots, and sort of just shapes, and just seeing what comes up. And even though they’re not far away from one another, each one has its own little palette of plants. It’s its own little world. It’s so interesting. The seed bank under the ground in each spot is different. So that’s why, I guess, I loved your circle idea because if I did that here, I know it would be very different from spot to spot. Yeah.

Joan: Yeah. Chance really plays a big role.

Margaret: Yes.

Joan: Chance… If you have one seedhead from an aster or a brown-eyed Susan fall in a spot and take root, yeah, they could just look totally different.

Margaret: Yes. Not to mention some of the less desirable things like Oriental bittersweet [laughter] and privet, and oh my goodness, all those naughty things.

Joan: Right.

Margaret: So at this time of year, and in the months ahead, a lot of the birds we each are going to see are… We think of as our feeder birds. And I don’t know, do you put up feeders? Can you do that all year round? Or do you… I have bears, I said in the beginning, so I don’t feed except in the coldest months. Do you feed birds at your place?

Joan: I do put up feeders. I put up feeders in Michigan in the summer, and I put up feeders in St. Louis when I’m there. And I know there’s a lot of discussion about feeders. I’m really careful to clean my feeders and to be sure that, if I ever saw a sick bird, I would take them down.

Margaret: Right.

Joan: But I haven’t seen sick birds. I haven’t seen any of those deformities that people talk about. And I guess I feel like the advantage to a feeder is it brings them closer and it can enrich your life and it can make people fall in love with the birds. [More: Best practices for bird feeding.]

Margaret: Yes. And everybody’s got to eat [laughter]. And so some of the birds, some species will come to the feeders, and some will be underneath the feeders, and everybody has their… So that’s something you can observe. And in your previous book, you talked about some of the behaviors and so forth around that. But in the new book, in “The Slow Birding Journal,” I don’t know why, but as I was reading, I kind of… These profiles of the different birds, I think there are 16 birds maybe in it, is that right? Did I make that up?

Joan: Yes, that’s right. Yeah,16.

Margaret: Yeah. I was noticing, oh, O.K., so you talk about the cedar waxwings, and they’re frugivorous or whatever—they eat fruit. And you were talking about different birds and what they eat, and I thought maybe we could talk about some of those and some other aspects of it. Like for example, with the waxwings, I have a lot, a lot, a lot of winterberry bushes, maybe 40 or 50 of them, old, old, old ones in groups around the property. And at some point everybody will swoop in, and it’ll be like, they’ll strip them in five minutes [laughter]. And I think of them as flocks. But I think in the book you talk about, in the case of a few of these different bird species, about the notion of a flock. How big is it? And what does flocks even mean? Because we say it about birds, but they don’t all even really aggregate in groups that way, or big groups that way, the way that starlings you might see.

Margaret: Yeah. I was noticing, oh, O.K., so you talk about the cedar waxwings, and they’re frugivorous or whatever—they eat fruit. And you were talking about different birds and what they eat, and I thought maybe we could talk about some of those and some other aspects of it. Like for example, with the waxwings, I have a lot, a lot, a lot of winterberry bushes, maybe 40 or 50 of them, old, old, old ones in groups around the property. And at some point everybody will swoop in, and it’ll be like, they’ll strip them in five minutes [laughter]. And I think of them as flocks. But I think in the book you talk about, in the case of a few of these different bird species, about the notion of a flock. How big is it? And what does flocks even mean? Because we say it about birds, but they don’t all even really aggregate in groups that way, or big groups that way, the way that starlings you might see.

Joan: Yeah. Well, many birds do group, and other birds are territorial, and birds like cedar waxwings are the perfect example of a bird in which grouping pays, because they’re going for fruit, and if they find a fruit tree, there’s enough for everybody. So it’s better they kind of fly around and let each other know, “O.K., here’s a fruit tree.” Whereas territorial birds, eating resources that may be more limited, wouldn’t want everybody to come.

But as long as you mentioned flocks, I just have to say that I just gave to my publisher another book called “The Social Lives of Birds,” and the first chapter is all about flocks. That’s the first chapter of the new book, and it was a lot of fun to write.

Margaret: Oh, that’s funny. And not P-H-L-O-X, but F-L-O-C-K-S [laugther]. Not the plant.

Joan: Exactly. Not the plant.

Margaret: O.K.

Joan: The plant is lovely, but… Yeah.

Margaret: Yeah. So as I said, the cedar waxwings will come in a group, and that makes sense. So they’re kind of on the reconnaissance mission as a group. Somebody finds the fruit and goes, “Hey, let’s go get the fruit,” and there’s plenty of fruit anyway when they find a source, so it works in both ways.

But for instance, you talk about flickers, one of my favorite birds, they’re just so beautiful, and they eat ants. Maybe they should have been called anteaters, but that name was already taken. And it’s just so… I’ve seen multiple ones in a stretch of lawn foraging at the same time, but they’re not a flock, right? Even if there’s three of them or something, they’re not together necessarily.

Joan: One of the things I learned about flickers is, just because there’s three there, does not necessarily mean they’re a family. Ants are an abundant and ephemeral resource, and it’s just really surprising that such a seemingly big bird… All birds are smaller than you think, because they have all those feathers, but… Yeah. That they could just eat those tiny ants. You’d think they’d have to be eating night and day, but… Yeah. It’s hard to say what’s a flock and what’s a family, unless you see someone feeding someone else, and then it’s like, oh, that’s a family.

Margaret: Yes. Yeah. But I think in the book you said something like, if you saw two flickers feeding on the same lawn, it might be more like unrelated people in line at the taco truck [laughter].

Joan: Exactly. Yeah.

Margaret: Which I loved. Yeah. And it might just be because there’s a lot of good ants up there.

Joan: Right. Yeah. Yeah.

Margaret: It is, it’s a beautiful bird. A beautiful, beautiful bird. Is it our second-largest woodpecker after the pileated? Is it the second-largest one? I was thinking it must be. Probably is. I think you even may say that in the book. Yeah.

Joan: O.K.

Margaret: They’re a pretty good size. I mean, it’s a pretty good size.

Joan: They are. Yeah. I was just going to say that it’s Karen Wiebe that has done all of the amazing work on flickers, and I hope she’s here at this meeting. She’s just been fearless at climbing into trees that have hollows, and making little doors, and just following the whole lives of the flickers, and it’s just really impressive.

Margaret: Interesting. Wow. That’s a life’s work. So speaking of things to eat, not ants, but songbirds, the Cooper’s hawks, and the sharp-shins I guess, too, but the Cooper’s hawks are in your book, in “The Slow Birding Journal,” the new book. You say that it takes 66 birds or small mammals to raise a single chick if you’re a parent Cooper’s hawk. I mean, that was pretty amazing [laughter]. That was a pretty amazing fact.

Margaret: Interesting. Wow. That’s a life’s work. So speaking of things to eat, not ants, but songbirds, the Cooper’s hawks, and the sharp-shins I guess, too, but the Cooper’s hawks are in your book, in “The Slow Birding Journal,” the new book. You say that it takes 66 birds or small mammals to raise a single chick if you’re a parent Cooper’s hawk. I mean, that was pretty amazing [laughter]. That was a pretty amazing fact.

Joan: Yeah.

Margaret: So they’re on the hunt looking for songbirds to eat. And this horrifies a lot of people.

Joan: Yeah. Yeah. You know, it’s nature. And most of the songbirds they catch are hatch-year birds, and… Yeah. It’s just how life goes. They also, kind of entertainingly, in the mating season, the males will bring in food and trade matings for food.

Margaret: Ooh! Bribe her with an expensive dinner. Is that the deal? Oh, my.

Joan: Yeah. And they can mate many, many times, each time for a different little morsel.

Margaret: Oh. Crazy.

Joan: Another thing that’s fun about Cooper’s hawks is, they don’t take their prey apart right at the nest. They have these things called plucking posts, and I found one in my neighborhood a couple of years ago, and they would always fly there, and they would dismember their prey, and drop the pieces they didn’t want, and then carry it to the nest, which would usually only be a few hundred yards away. So it’s fun if you can find a plucking post. Or maybe it’s grisly, I don’t know. It’s just…

Margaret: Well, I used to be horrified by it many years ago, and I remember a long time ago, Pete Dunne, the ornithologist who’s written a number of books over the years, including one about hawks, he said to me, “Well, you saw it, Margaret, because it was at your bird feeder. You saw it swoop in and do this.” But it wasn’t like you caused it. It was going to need to get that songbird anyway, because this is a food chain.” And I think you point out in your new book, you point out, hey, that songbird, by the way, to raise one of its young, will eat how many thousands and thousands and thousands of insects, or use thousands and thousands and thousands of insects to feed its young, each one of its young. So it’s a food chain.

Joan: Yeah.

Margaret: So he was saying, this is not something horrifying or scary or awful. This is the way the system works, and has always worked.

Joan: And when it’s out of balance, like with the deer… And I’m in Colorado right now at this YMCA of the Rockies, and they have elk right between the cabins. We walk past elk every day. And these large ungulates that no longer have their natural predators really change the landscape. And scientists can see that when they fence in areas, and they can see trees that just don’t make it when there’s deer or elk can thrive if they’re kept out.

And at my summer home in Michigan, they’ve been doing some very interesting exclosures, where they see trees that you don’t see maturing are able to do so when the deer are excluded. So… Yeah. We mess with the balance at our… It’s our risk to mess with it.

Margaret: Yeah. At our peril. Yeah. So I was reminded, I guess I knew it a long time ago and I had completely forgotten, the reason that a male cardinal can be so vividly red is dietary, is based on what he eats, yes?

Margaret: Yeah. At our peril. Yeah. So I was reminded, I guess I knew it a long time ago and I had completely forgotten, the reason that a male cardinal can be so vividly red is dietary, is based on what he eats, yes?

Joan: Right. Yes, yes. Yeah. They eat red plants, they eat things with carotenoids, and there, that’s again something that we’ve changed. As we have planted more plants that naturally have red berries, it’s a less clear signal to the females that this is a high-quality male. It’s kind of like if diamonds suddenly became… I mean, not that we judge our males by the ring they give us [laughter], but… Of course we don’t. I don’t even have a diamond, and I’ve been married for decades.

Margaret: But the male cardinal, the more of these carotenoids he ingests, such as from fruit, he becomes redder and redder, and the female would be more attracted to a very red male, one that looks like a good candidate for reproduction, I mean, right?

Joan: Right. Right. Yes.

Margaret: She wants the fittest one. Yeah.

Joan: Right. Yeah.

Margaret: Yeah. And then blue jays… I just want to talk about blue jays a little bit. Blue jays sizing up the acorns, and you see them, the acorns are dropping, and some have dropped and so forth this time of year, and the blue jays kind of… They don’t just take any old acorn; don’t they size them up for quality? It reminded me of me in the store at this time of year, in the food co-op, picking up each of the winter squash to feel which is the heaviest for its size. Do you know what I mean? Like I’m looking for the best one.

Margaret: Yeah. And then blue jays… I just want to talk about blue jays a little bit. Blue jays sizing up the acorns, and you see them, the acorns are dropping, and some have dropped and so forth this time of year, and the blue jays kind of… They don’t just take any old acorn; don’t they size them up for quality? It reminded me of me in the store at this time of year, in the food co-op, picking up each of the winter squash to feel which is the heaviest for its size. Do you know what I mean? Like I’m looking for the best one.

Joan: Yes. Yes.

Margaret: The blue jays do that, too, don’t they?

Joan: Yeah. I mean, they don’t want an acorn that’s got weevils in it. And so if a weevil has eaten out the acorn, yeah, it’ll be lighter, and so they figure that out. They also take the cap off. They can only carry a few in their throat, and they fly away, and they bury them, to our benefit, because I think they were important in moving the forests north after the glaciers subsided in much of the country, much of the northern part of the country. And that was really 10,000 years ago for a… It’s just not really that long ago.

Margaret: Right. In the big picture, right? And I think you suggest an activity in the book that we could kind of look to see where are their acorns around now, not just under the tree where they would have fallen, but do we observe some that have been maybe picked over and moved or whatever, or just moved to a new spot; to really go around and look and think about the work that’s being done.

Joan: Yeah. And we can also see if we’d make a very good blue jay and judge the acorns, and maybe cut them in half and see if we inadvertently picked some weeviled ones. Yeah.

Margaret: Yeah. I wanted to tell you about a kind of bittersweet bird story I had last winter when at my feeders, a Wilson’s warbler, who doesn’t even spend fair weather here, let alone the snowy winter, a Wilson’s warbler male suddenly appeared at my feeders in the winter, and spent the winter here in middle New York State, not where he was meant to be. And these accidental things that happen. I don’t know if you’ve had that happen, where someone maybe got moved off course in a stormy activity in the migration or something like that, and ended up in the wrong place. It was very… Again, it was beautiful and wonderful, and to watch him adapt to eating among all the other birds and to eating seeds, which isn’t really his thing.

Joan: Wow. No, not at all. That’s astonishing.

Margaret: He became a ground feeder for the entire winter, under the… Once he sort of scoped it out, and it was fascinating, but it was also heartbreaking. And the first snow came, and I was out there with him, and he’s eating on the ground in the snow, and I’m just kind of watching, and… Beautiful, but again, heartbreaking. So the world is changing. And I guess that probably always happened, but it was a privilege, but also kind of upsetting, you know?

Joan: Yeah. I mean, evolution works on a slow timescale, and what’s happening to our planet right now is on a fast timescale, and organisms don’t adapt, they mostly perish.

Margaret: Yeah. Yeah. So anyway, that’s my little odd story, but I’m always glad to talk to you, and I wish we could go birding together [laughter].

Joan: Yeah. It’d be a lot of fun.

Margaret: Here in the yard, or in your yard.

Joan: Yes, it’s my pleasure. Thank you.

(All illustrations from the book, “The Slow Birding Journal,” used with permission.)

enter to win a copy of ‘the slow birding journal’

I’LL BUY A COPY of “The Slow Birding Journal” by Joan Strassmann for one lucky reader. All you have to do to enter is answer this question in the comments box below:

Are you a slow birder, and what bird do you feel you know best?

No answer, or feeling shy? Just say something like “count me in” and I will, but a reply is even better. I’ll select a random winner after entries close Tuesday Oct. 29, 2024 at midnight. Good luck to all.

(Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

prefer the podcast version of the show?

MY WEEKLY public-radio show, rated a “top-5 garden podcast” by “The Guardian” newspaper in the UK, began its 15th year in March 2024. It’s produced at Robin Hood Radio, the smallest NPR station in the nation. Listen locally in the Hudson Valley (NY)-Berkshires (MA)-Litchfield Hills (CT) Mondays at 8:30 AM Eastern, rerun at 8:30 Saturdays. Or play the Oct. 14, 2024 show using the player near the top of this transcript. You can subscribe to all future editions on iTunes/Apple Podcasts or Spotify (and browse my archive of podcasts here).